- Home

- Barbara Egbert

Zero Days Page 12

Zero Days Read online

Page 12

Many casual hikers we met along the trail assumed there is some sort of master plan for thru-hikers to reach the optimal daily intake of calories, fat, carbohydrates, protein, and vitamins—sort of like a food pyramid for backpackers. But there are nearly as many menu plans as there are individual hikers. There are a few main themes. Some backpackers—probably more than in the general public—are vegetarian or vegan. Some go without stoves, which means they can’t use the dehydrated food most of us eat. Some spend much of their pre-trip time preparing their own food, while others—us, for example—rely almost entirely on store-bought items, supplemented with a daily vitamin pill.

K-Too of Massachusetts is one of the home cooks. He made vast quantities of spaghetti sauce and dehydrated it. He also bought fruit in season during the months leading up to his trip out West and dehydrated that, too. One of his favorite dinners was instant mashed potatoes topped with a packet of tuna fish. K-Too liked variety in his morning meals, so at town stops, he would buy different kinds of dry cereal, mix them together, and top them off with dried fruit and almonds. For breakfast, he would have a serving of the cereal mixture topped with Nido, an instant whole milk product. (Most instant milk is nonfat.) Although he rarely eats meat, K-Too is honest about needing an occasional serving of animal protein—especially after recovering from giardia in northern California. “I skipped up to Ashland (Oregon) and got cured,” he recalls. “I hadn’t eaten prime rib in 15 years, but after losing so much weight, I had one at Camper’s Cove.” On one occasion, a stranger presented him with a dozen eggs on the trail. Luckily, two other backpackers found him standing there with this unexpected but impractical bounty, helped him cook the eggs, and then helped eat them.

Bald Eagle and Nocona, the engineers from Texas, typically began their day with Clif bars. “I also liked Carnation instant breakfast with Nido,” Bald Eagle says. They drank Emergen-C, a vitamin-packed drink that he describes as “a fizzy cocktail.” Their second breakfast typically consisted of Snickers bars and nuts. Lunch was jerky and Pringles. “I love Pringles!” Bald Eagle exclaims. “And after you eat them, you can use the can to hold trash.” The day’s meals continued with bread and cheese if they had recently made a town stop where they could purchase such perishables. Nocona learned to pack bread without crushing it too much. Also welcome on the trail: tortillas and what Bald Eagle describes as “super-nitrated summer sausage.” The evening meal was frequently pasta with dehydrated vegetables and olive oil. Packaged tuna, clams, or oysters went on top. Dessert was more candy or gummy bears. This sounds like an enormous amount of food. Yet, by the time we got to know Nocona and Bald Eagle in northern California, they had each lost about 35 pounds.

We lost weight, too. Gary and I each shed about 20 pounds. Mary lost only 7 pounds, but considering she weighed only 70 pounds and had no body fat when we started hiking, that worried us. We always urged her to eat more. At the beginning of a trail section, when our packs were heavy with the contents of a resupply box, I consumed roughly 3,100 calories a day. Gary probably ate about 3,400. Mary’s total per day was around 1,850. Our caloric intake dipped a bit toward the end of each section, as we ran low on the highest-calorie chocolate bars.

Scott Williamson, the first yo-yo finisher, is one of the few backpackers we met who knew precisely how many calories he consumed in an average day on the trail: 3,500. However, he estimated that if he wanted to replenish the calories he expended, he would have to eat 5,000 calories, a nearly impossible task. “If I eat 5,000 calories a day, it slows me down,” he explains. “My body uses so much energy to process the food.” Also, 5,000 calories would equal about 4 pounds of food, far more than the 2 or 2.5 pounds a day backpackers tend to aim for. There’s a point at which the weight of extra food is more than a hiker can carry and still make the miles.

So if he eats 3,500 calories per day but burns up 5,000, how does he make up the difference? “I pig out in town—I’m famous for that,” he says. But he doesn’t indulge on the trail. Scott goes for the healthy stuff: dried beans, dried fruit, bagels, and cheese. “I don’t eat much sugar and candy on the trail. It messes up my rhythm to eat too much sugar,” he says. Scott, who at the time of our hike made a living by trimming trees during the off-season, says it takes more than calories to keep going. “Calories are important, but if calories were enough, we could just hike with sticks of butter,” he says. “We need nutrient-dense food with vitamins and minerals. The two foods I really craved on the trail were spinach and red meat—two foods with lots of minerals.” Scott was a vegan for several years—no meat of any sort and no animal products, such as cheese or eggs. However, he was a carnivore like most of the rest of us when he completed his yo-yo.

Thru-hikers like K-Too who choose to prepare their own dehydrated food at home have to start the process way ahead of time, washing, peeling, and slicing quantities of fresh fruits and vegetables, and cooking up vats of spaghetti sauce, then drying everything and sealing it in plastic. We had no interest in adding another difficult, time-consuming task to our long list of difficult and time-consuming pre-trail chores, so we skipped that route. Others order five-month supplies of protein powder, whole-wheat pasta, powdered soy milk, tofu jerky, and other really healthy foods. We knew they ordered huge amounts because we kept coming across Ziploc bags full of this stuff in hiker boxes all the way north along the trail. Hiker boxes are where backpackers shed the food items they’ve grown tired of, with the idea that a subsequent backpacker who has become sick of entirely different items will decide to make a switch. Hiker boxes are also useful for people whose supply boxes fail to arrive in the mail, as well as those who try to resupply at stores along the way, only to discover that the previous three days’ worth of dayhikers and tourists had bought up everything except canned pears and fishhooks.

Gary and I had been happily eating freeze-dried dinners since he took me on my first backpacking trip in Shenandoah National Park in 1988. I was exhausted and covered in bug bites after a strenuous day in Virginia’s typically hot, humid, and mosquito-infested summer weather. Gary set up his tiny stove on a ledge overlooking a forested valley, boiled some water and presented me with my first freeze-dried meal. It was called Spinach Florentine, or something like that, contained rice (or was it noodles?), and while it’s no longer manufactured, I still count it among my top 10 favorite flavors. Mary is less enthusiastic about freeze-dried food, but she did develop a taste for the organic dinners from Mary-JanesOutpost, especially the buttery herb pasta.

When it came time to order food for the PCT, we wanted a variety of dinners we could all eat for five or six months without getting too tired of any of them. We came pretty close. Our one mistake was ordering about a dozen packages of a pasta dinner with sun-dried tomatoes. We’d eaten it once, and I thought we all liked it. But the first time I cooked it up on the PCT, we discovered it was too spicy for any of us. For the rest of the trip, any time I came across that dinner in a resupply box, I mailed it back to my sister or left it in a hiker box. To make up for the missing dinner, we’d buy a couple packages of ramen noodles, available at practically every store in the known universe. (Mary never developed a taste for ramen. She loathes every variety, from “roast chicken” to “oriental” flavor.)

“Waste not, want not” certainly applies to long-distance backpackers. After Kennedy Meadows, we realized we needed more protein on the trail, so I bought peanut butter in squeeze tubes and put one in each resupply box. It was a big hit. And after we had squeezed all the peanut butter we could out of the tube, I would take my Swiss Army knife and cut the tube open. Then we would pass around the messy, dissected container to get every last possible molecule out of it. How to get that final bit was one of the few food-related issues Gary and I disagreed on. He insisted the best way was to cut off the top and squeeze from the bottom. But I was the one with the knife, and I insisted on carving up the tube as though I were butterflying a steak. It turned out not to make much difference. We also bought a lot of dried fruit,

thinking we needed more vitamins and minerals. This didn’t work as well. More than a little bit of it gives me the g.i. trots, and none of us really cares for dried fruit all that much. I ended up sending bags of dried cranberries, raisins, and “dried plums” (the food industry’s new name for prunes) back to my younger sister, who saved most of them for us despite our generous suggestion that she serve them to her family. When we returned home, after trying out various recipes, I ended up mixing most of the fruit into scones. We ate most of the nuts we brought along, generally salted cashews or mixed nuts. And we never wasted a single Pringle. We realized in our first seven weeks how much we liked them. So when we packed our resupply boxes for the second leg of the trip, we bought enough for a tube every day. I tried to organize them in such a way that we never had the same flavor two days in a row. We alternated among original flavor, ranch, pizza, cheddar, sour cream, and barbecue. Gary never got sick of Pringles, and only wished there were more flavors. He saw a can of “ketchup blast” Pringles at a store in Kennedy Meadows, and one of his chief regrets in life is that he didn’t buy it. We never saw that flavor again, although I believe it’s been on sale in Canada. How that container ended up in a little store in the southern Sierra is one of those mysteries of the market we’ll probably never solve.

Once we got to a town, our low trail-food standards dipped even lower. McDonald’s, Burger King, or whichever fast-food joint was within the shortest walking distance became our Chez Panisse for the day. Mary in particular dived into burgers, fries, and malts with surprising intensity. Sometimes she even ate more than I did. And this from a child who had to be cajoled into eating when we were at home, and who periodically considered going totally vegetarian.

Our first trip away from the trail to visit relatives in Carson City was an eye-opener for my family. My brother, George, picked us up at Kennedy Meadows after our first seven weeks and 700 miles. Soon, we were speeding north on U.S. Highway 395 along what was literally a moveable feast. At Lone Pine, we stopped at McDonald’s and stuffed ourselves. At Bridgeport, we stopped at the Sportsmen’s Inn and gorged some more. George had a bite in Lone Pine but just ordered coffee in Bridgeport, sipping it while watching with a bemused smile as his relatives turned into a shoal of great white sharks. And when we reached Carson City, we raided my sister Carol’s refrigerator with grim determination.

That thru-hikers are focused on food isn’t odd considering the calorie deficits we build up. There is no way—simply no way—most hikers can carry enough food to meet their needs. I say “most hikers” because once in a great while we came across thru-hikers who claimed they couldn’t eat all the food they were carrying. (We stole their food and then killed them and ate them, too.) The result of this chronic starvation diet is a fascination with calories that would gratify a Weight Watchers instructor, but with one big difference: Thru-hikers read the nutrition labels to find the most calories and the most fat. I used to wonder why Snickers bars are the universal favorite lunch among long-distance backpackers. A look at the fine print on the label cleared that up: At 280 calories, Snickers bars pack major calories in a small package, and they’re on sale at every dinky little store along the PCT.

Our food obsession came as no surprise, although it was more intense than I expected. We ran into this on our first Tahoe Rim Trail trip in 2001. The Tahoe Rim Trail follows the ridges around Lake Tahoe, which straddles the Nevada-California state line west of Carson City. We were among the first 100 people to backpack its entire 165-mile length in one trip, and Mary was the youngest to complete it. For the first few days of that 13-day outing, our conversations centered on whether we could even keep going, what with my initial weakness, Mary’s spell of sickness, and the onset of serious foot problems for both Gary and me. Once we agreed to keep going, our thoughts turned to other topics: the scenery, the people we met, but primarily the food we were going to consume once we got off the trail. Mary and I began a hobby, which we continued on subsequent long hikes, of making up new food items and recipes. You’ve heard of French silk pie? We invented burlap pie and denim cake. Fruit smoothies are good, but we went one better, inventing new beverages using weird combinations of fruit, ice cream, and even coffee. (We only tried one of them at home: Gary’s suggestion for a banana-mint blender drink. We used fresh bananas, mint-chocolate chip ice cream, and fresh mint leaves. Wasn’t half bad.)

Our food preoccupation on that trip became more pronounced as we rounded Lake Tahoe’s north end and headed down the Nevada side toward our finish line at Kingsbury Grade. We had three or four days to go when I took inventory of our food stocks at Mud Lake. Our appetites had increased remarkably since our resupply at Tahoe City, California, and while we had enough instant cocoa for breakfast and freeze-dried meals for dinner, we were woefully short of everything else. Strict rationing only emphasized our hunger.

Luckily, we enjoyed a little trail magic at Spooner Lake, although we didn’t even know the phrase at the time. We made a detour to the lake, near U.S. Highway 50, to get water from the state park’s faucets. After filling our bottles, we sat in a sunny spot to rehydrate and eat tiny smidgens of turkey jerky, plus a few M&Ms apiece. As corpulent tourists wandered around, we fantasized about knocking them down and stealing their picnic lunches. Fortunately for them, I went in search of a trash can and came across something even better—a sign promising ice cream at the end of a paved path. Was I hallucinating? There, just a few yards away, was a store run by Max Jones, a member at the time of the Tahoe Rim Trail Association board of directors, catering to the summer mountain bikers and the winter cross-country skiers. I ran back to get Mary, who was soon in ice-cream-sandwich heaven while I ran up a tab of $30 or $40 worth of energy bars and chocolate. Gary had stayed behind with our packs, but he made up for lost time as soon as I returned with the goodies. He has a vivid memory of standing in front of the water fountain, a candy bar in each hand, eating them alternately and voraciously, while a woman picnicking nearby tried to persuade her kids that they needed to eat their carrots and apples so they could grow up to be strong and healthy.

We created a similar scene during the sixth week of our PCT trek. We had spent much of a hot day meandering through the Tejon Ranch, where the trail zigzagged all over creation on its way toward the Tehachapi hills and the southern Sierra, because the ranch owners at that time wouldn’t let the PCT run straight across their land. At the next highway crossing, we learned that a 1-mile detour would take us to the aptly named Country Store. After some discussion, we decided to go for it. (It’s hard to believe we even had to discuss it, but our feet hurt all the time and extra steps weren’t welcome.) Once at the store, we bought scads of cold drinks and ice cream, which we consumed on the shady porch, and left with lots more of the less perishable items in our packs—$40 worth, in all.

One thing we didn’t consume on the trail was coffee. We knew we wouldn’t have time to make coffee every morning, we didn’t want to suffer caffeine withdrawal on the trail, and we didn’t want to have to drink extra water to make up for coffee’s diuretic effects. Gary and I gave up our daily cup or three before we started the PCT. We both quit cold turkey.

Here’s how I sounded the day I gave up coffee:

“Ooooohhhhh, Gary, I’m miserable! Oooohhhh. I’ve gotta lie down … oh, please get Mary ready for school. I can’t even stand up. Oooohhhh …”

Fortunately, caffeine withdrawal wasn’t responsible for all of that misery. On a February weekend, we had gone backpacking in Henry Coe State Park for two days, preparing for the PCT, and I drank instant cocoa instead of coffee. The day after the trip, I got up as usual to help Mary get ready for school, and promptly collapsed on the bedroom floor. I don’t know what hit me, but it hit awfully hard—flu, probably. I didn’t drink coffee for two more days while I got over the whatever-it-was. And by the time I felt better, I figured I might as well remain coffee-free, since I’d already gone through involuntary withdrawal. It was a relief—I had been dreading the headaches that s

ometimes accompanied me to work without caffeine. A month later, it was Gary’s turn to get sick, and he also took advantage of the opportunity to quit coffee. We also gave up alcohol, but that was easier. Gary rarely had anything to drink, except on social occasions, when he would down a few beers. I had been in the habit of drinking the heart-healthy quota of 3 or 4 ounces of red wine each night. A few weeks after the first of the year, I bought my last bottle. When I ran out of wine, I just didn’t buy any more.

During our months of trail-enforced food deprivation, we occasionally experienced the kind of serendipity that made me believe in manna from heaven. One such event occurred in early July on a day of snow and rain showers a few miles north of Muir Pass. We were running short of food and were still a couple days away from our next resupply. We had walked several yards off the trail for a rest break in the shelter provided by a trio of gnarled juniper trees. We usually made so much noise no one could miss us, but this day, for some reason, we kept quiet as two people walked on the trail nearby. They spotted us anyway, and came over for a sit-down break to introduce themselves. Paul and Alice were hiking the John Muir Trail and, by some miracle, they had actually packed too much food. They offered it to us. Showing great restraint, we accepted only what they really, really didn’t want. Honest, they insisted they didn’t want it—cookies, crackers, pretzels, peanuts. Scrambler’s journal entry that night reflected our delight:

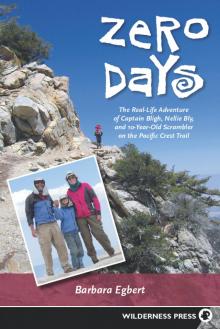

Zero Days

Zero Days