- Home

- Barbara Egbert

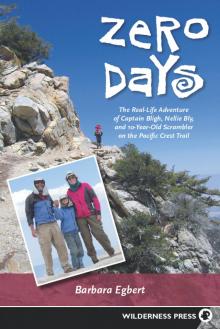

Zero Days Page 14

Zero Days Read online

Page 14

PACIFIC CREST CAFE: A “RESTAURANT” REVIEW

As evening falls on the Pacific Crest Trail, hungry diners can’t do better than to try out this delightful eatery, with its woodsy ambience and rustic influences. Although not quite up to white tablecloth standards, the Crest still manages to combine friendly and helpful service with a surprisingly robust choice of entrees. The exuberant menu varies depending on the contents of the last resupply box, but diners can always be certain that the ramen noodles will be piping hot and the freeze-dried dinners competently stirred.

On a recent night, a festival atmosphere imbued the cafe, as a party of three celebrated the recent accomplishment of a 25-mile day, with the added excitement occasioned by reaching an adequate campsite before dark. The occurrence of random piles of dried cow dung interfered only slightly with the overall aesthetics, as the fall of night soon enabled visual distractions to disappear into the dusk. National Park Service rules precluded the lighting of campfires, but the hiss of a small but energetic backpacker’s stove sufficed to drive away any gloom that the incipient twilight might bring.

This evening’s repast began with steaming hot mugs of cocoa. The choice of Nestle’s instant over the competing Carnation product may not have been the absolute best one, but the chef’s decision to serve the beverage in transparent acrylic cups allowed the diners to ensure that every crystal of sugar, every molecule of alkali-processed cacao bean, and every delectable tidbit of partially hydrogenated tropical oil was appropriately dissolved. The rather undistinguished presentation of the hot chocolate on bare ground was nicely offset by the gradual appearance overhead of the summer sky’s constellations.

Next to appear were the two entrees: ramen noodles, served in a titanium pot, and three-cheese lasagna, modestly presented in a waterproof bag. While the chef’s choice of an Oriental vegetable flavor of ramen to accompany the decidedly Mediterranean nuances of the lasagna seemed incongruous at first, the two made for a surprisingly good pairing. As all experienced backpackers know, ramen is simple to prepare, while freeze-dried dinners can be more challenging. In this case, my spork was able to turn up only a half teaspoonful at the most of unincorporated powdered mozzarella—a notable accomplishment for a cook lacking all but the most rudimentary of culinary utensils.

I can say nothing but good about the 2004 vintage California snowmelt vin d’tres ordinaire (estate bottled) served with dinner. Despite its humble packaging in re-used Albertsons water bottles, their paper labels in a severe state of disrepair, this spring-fed beverage (appellation Ansel Adams) was served at precisely the correct temperature and in exactly the right amounts.

The dessert, a chocolate mousse, was extravagant by backpacker standards. The triumphantly outrageous concoction of freeze-dried chocolate and paper-thin Yolo County almonds was a suitable confectionary counterpoint to an evening of dining al fresco.

Reservations required.

CHAPTER 6

THE WORLD OF NATURE

Day 56: Today we started late. We repacked everything for a “formidable” stream crossing. We saw beautifully breathtaking scenery high up and heard coyotes barking. We also saw marmots standing like sentries. We also saw large rabbits, and at our beautiful tent site, wonderfully colored clouds.

—from Scrambler’s journal

WATCH ALL OF THE NATURE PROGRAMS on television, visit zoos and museums, read Backpacker and Outside and National Geographic—and you won’t come even close to the experience of actually moving out of the house and living under the conditions of the natural world. Weather is no longer something you shelter from in a house or car or under an umbrella. It’s something you walk in, eat in, set up camp in, sleep in. The animals that ordinarily are occasional treats to see, or occasional nuisances to avoid, suddenly become a major part of life, inescapable. Living inside nature, not just observing it, is one of the greatest pleasures of backpacking. It can also be one of the biggest drawbacks. Just ask people who have been struck by lightning, caught in early-season blizzards, mauled by bears, or who otherwise have fallen victim to Mother Nature’s darker side. Even experienced outdoorsy types still ask me how we checked on the weather forecast while hiking the Pacific Crest Trail, and they are taken aback to learn that, except during town stops, we had no way to do that. Like the pioneers of old—the Donner Party leaps to mind—we had to put up with whatever came along.

When we left the Mexican border in early April, the creatures we worried about the most were of the two-legged variety: Border Patrol agents who might question our identities and plans, and illegal immigrants who, rumor had it, might steal our water. The Border Patrol did take an immediate interest in us, but that didn’t last long. As we traveled north, the Forest Service and even sheriff’s deputies kept an eye on us. Our worries about being able to prove our citizenship status faded as we continued farther north, while rattlesnakes, bears, mountain lions, and mosquitoes loomed larger on our list of concerns.

The common perception of the desert as a barren place with few animals was disproved right from the beginning. Every day we would see hummingbirds, quail, or crows; rabbits or maybe pika at higher elevations; and lizards and horny toads and boldly patterned king snakes. The list grew longer as we entered the Sierra. We quickly found ourselves growing fond of particular creatures like marmots, the large, furry rodents who live above treeline throughout much of the West. These relatives of woodchucks also symbolized the progress we had made on the trail. When we began seeing marmots, we knew we were truly in the mountains.

Mary named the marmot who greeted us at the top of the highest pass in the southern Sierra “Fed.” He looked remarkably like “Teddy,” the marmot who had shown up at that morning’s campsite. I always got out of the tent first in the morning, and began organizing our food and equipment, but only after a quick bathroom break. That particular morning, taking advantage of the privacy that came with being the first one up, I had chosen a spot just outside the rocks that marked the boundary of our spacious tent site, about 100 yards from Tyndall Creek in the southern Sierra. Later, after Gary and Mary had risen, Teddy the marmot showed up, and seemed obsessed with that particular damp spot. Gary speculated that a previous camper must have deposited food of some sort there—a big no-no in the backcountry, where leftovers are bound to attract vermin and possibly bears. With some embarrassment, I admitted that it was I who had made the deposit in question, and theorized that the marmot had been attracted by the salt in my urine. That didn’t leave all prior campers off the hook; Teddy’s comfort level around humans made us suspicious that he had received handouts from previous visitors to the well-used site. Mary was able to sit within a few feet of him and draw his portrait while he licked up the salt, although every few minutes he would run off, and then slowly work his way back.

With “Fed,” there was no doubt about his affinity for humans. He didn’t just tolerate us when we reached Forester Pass at 13,180 feet—he positively welcomed us. Fed hopped around the rocks in excitement, disappearing behind a boulder, then reappearing a little closer to where we sat with our packs, breathing heavily in the thin air at the highest point of the Pacific Crest Trail. We didn’t give Fed anything—in fact, we actively discouraged him from approaching the food we were wolfing down—but it was obvious that plenty of previous hikers hadn’t been such purists. Marmots are a favorite with many backpackers. They look cuddly, like stuffed animals, with lots of fur and abundant fat for a winter of hibernation. They have heads rather like puppies and they’re great fun to watch as they zip between their grassy feeding sites and their rocky hiding places. In 2002, when Mary returned from a trip up Mt. Langley in the southern Sierra with her Dad, she was full of stories about the marmots in the meadows near the campsite: their abundance, their behavior, their cuteness. When I accompanied both of them on another Langley trip a year later, I also became a big fan. (Marmots didn’t take the place of our two pet cats in our affections, but some came mighty close.)

Marmots had plenty of com

petition for favorite animal status. But there was no competition for title of most-hated. Mosquitoes won that contest, big time. Mary, like most girls, has a soft heart for animals. When daddy longlegs climbed into the tent, I had to catch them by the legs and pitch them outside, rather than just killing them, which would have been a lot easier. But soon after we entered the Sierra Nevada, Mary was swatting mosquitoes with abandon. A dead skeeter gladdened her bloodthirsty little heart. An evening’s entertainment consisted of smashing the nasty little critters that managed to sneak inside the tent, despite our efforts employing what Gary designated “mosquito protocol.” That meant that when it was my turn to get into the tent, for example, I would zip open the door just enough to park my fanny inside, while quickly taking off my boots outside. Then I would hastily roll into the tent and close the zipper. This helped, but not even a flamethrower could deter the Sierra’s mosquitoes from flying into a tent occupied by anything alive. The tent that had stayed so clean all through the desert rapidly became streaked with little bits of blood—our blood.

The only serious argument Gary and I had the first couple weeks in the Sierra involved Lanacane, the ointment we smeared on insect bites to ease the itching. He thought he had packed a full tube, but in fact it was only half full. I, on the other hand, had made the same mistake with the bottle of sunscreen. In the end, we had plenty of both with just a small effort at rationing. And by the time we reached northern California, we had quit using either one. I have always reacted strongly to mosquito bites, thus my anxiety at having inadequate Lanacane along. When I first met Gary in 1988 and went backpacking with him in Shenandoah National Park, I would go home after a two-day trip with dozens of bites, some of them swollen to the size of a quarter, and the itching would drive me crazy for a couple weeks. Somehow, my body adjusted to the plethora of mosquitoes in the Sierra, and itching was minimal. I had the same experience with poison oak. I’m normally extremely sensitive to it, but on the PCT, I just didn’t react to it. (Unfortunately, that immunity didn’t last, as I discovered the hard way three months after we returned home.) As for sunscreen, we plastered it on religiously in the southern desert, but I still got sunburned, and Mary did, too. By the time we reached the Lake Tahoe area, we found that a little on our noses and ears was enough. And despite months of sunshine, we neither tanned nor burned. (The thick layer of dirt we wore on our skins may have had something to do with that.)

The animal everyone talks about on the trail isn’t the marmot, or even the mosquito. It’s the bear. This creature forms a sort of leitmotif to every long trail. There are Bear Creeks and Bear Valleys up and down the PCT, and Black Bear restaurants off the trail in nearby cities. And wherever trail people gather, there are bear stories.

I began our PCT trip partly hoping we’d have a bear encounter worth sharing later, but mostly hoping that the only part of a bear we’d see would be its tail, rapidly receding in the distance. We had all read Bill Bryson’s A Walk in the Woods, with its opening tale of a 12-year-old boy being carried off and killed by a black bear in Quebec in 1983. Dayhikers who met us on the Tahoe Rim Trail in 2003 eagerly told us about recent bear attacks in western states. We had spent hours discussing how to protect our food from ursine marauders, eventually settling on the new, improved Ursacks that a California company manufactures from extremely tough fabric similar to what is used in bulletproof vests. Compared to hard-shell bear canisters, Ursacks worked well in terms of bear protection, and were vastly more practical on a long trip. We also avoided much-used campsites along the trail, knowing from experience that the more heavily used sites were more likely to have furry visitors. The only bear problem we had ever experienced before was during our Section I hike in 1999, at Glen Aulin High Camp, about 6 miles north of Tuolumne Meadows in Yosemite National Park. There, in the cloak of darkness on our last night, Ursus americanus snagged our food bag. Mary never forgot about that bear, which ate up the Gummy Bears she’d been saving for our last day. A package of freeze-dried chili and another of freeze-dried blueberries—mistakenly left in my backpack in our tent—provided us with our only food for that last day. What made the bear’s theft especially frustrating for Gary was the fact that he had carefully hung our food from a bear pole the night before. We concluded that the Glen Aulin bears had learned to shake the bear pole supports really, really hard whenever they saw food bags hanging from the crossbar, and our bag was the first one to fall.

Our closest 2004 encounter with bears occurred one day in late June, about halfway between Pinchot Pass and Mather Pass. The evening before, we had spent a long time looking for a suitable campsite—suitable meaning one that hadn’t been used before, was out of sight of the trail, and showed no signs of bear activity, such as fur or claw marks on the trees. We were beginning to worry we didn’t have enough food to get to Vermilion Valley, our next resupply and the only source of provisions on a very long stretch of trail. If we ran low, there was no place to get more, so we decided to go on short rations, beginning that evening. We knew we had to let nothing go to waste—or to bears. The weather was warm, so we went to sleep with the tent door pulled back, giving me a good view through the mosquito netting of the tree where Gary had attached our Ursacks about 5 feet off the ground with a chew-proof Kevlar line.

About 5 a.m., I awoke to a crunching sound. My first thought was of footsteps. A ranger on very early patrol? We had passed the Bench Lake seasonal ranger’s tent cabin the previous afternoon. It was fully light as I peered through the tent’s screen. But it wasn’t a ranger. It was a bear, big and furry and cinnamon-colored, the classic black bear of the backcountry, gnawing away at an Ursack. I shook Gary hard (he’s difficult to wake up and uses ear plugs as well) and shouted, “Gary, there’s a bear trying to get our food!” That got him out of bed. He scrambled out of the tent, with me right behind him, grabbed an ice ax, and shouted at the bear to get away. Unimpressed, the bear kept gnawing. “Get some rocks!” Gary ordered. Wouldn’t you know, that site was practically bereft of rocks. After all the time and effort we’d spent moving rocks out of other tent sites, all I could find here were soft, half-rotten pinecones. Also, I was barefoot and walking was painful. After some scouting around, I managed to find four or five rocks, which I handed to Gary, who heaved them near (not directly at) the bear while continuing to shout. The idea was to scare the bear without injuring it; Gary figured actually hurting the animal might inspire it to hurt him back. Luckily, the bear was scare-able, and after a few suspenseful moments, it dropped down on all fours and ran off. By that point, Mary was wide awake and watching the action from inside the tent. We gave her strict orders to stay put.

Breathing hard from the excitement and sudden exertion, Gary and I climbed back into the tent and wriggled into our sleeping bags to rest. And 20 minutes later, the bear was back—with a friend. Another couple rocks, and the original visitor lumbered off, but the newcomer was made of sterner stuff. This one, although smaller than the first, was also grumpier, growling at Gary as it continued gnawing fruitlessly on an Ursack. It took several more stones and a lot of shouting to send it on its way. Or perhaps it was the sight of Gary in his navy blue long johns that frightened it off. But finally, go it did, and we felt safe enough to exit the tent and eat breakfast. The bears had failed to open any of the Ursacks or gnaw through the Kevlar line. One bear left a set of fang impressions on the bag containing the garbage, which we proudly showed off to other hikers all the way north.

In July, in a wilderness area south of Yosemite, a ranger we met was the only person who ever asked to look at our permit. She also asked to see our bear canisters. Acknowledging to her that we knew about the canister requirements, Gary explained why we were carrying Ursacks instead. She let us off with a warning, which we considered very generous. But the fact is, we were willing to risk a fine just to avoid using canisters, which we had used in the past and discovered to be cumbersome and too small. Ursacks (especially the newer versions, which have been redesigned to thwart bears even more

effectively than before) suit us much better. Rangers always have blood-chilling bear stories to tell backpackers, in an effort to encourage compliance with food-storage rules. This ranger told us bears have become so accustomed to finding food in tents that they’ll walk right in, whether there’s any food there or not. That seemed to suggest it was immaterial whether campers stored their food properly. But we didn’t argue. We like rangers, we just don’t like the bear-canister regulation, which they’re required to enforce.

A week later, in the little California town of Bridgeport, we had our first encounter with the thru-hikers we came to call the Friendly Four: Nocona and Bald Eagle, a married couple from Texas, and Crow and Sherpa, two women who at that time lived in Colorado. They’d had more bear encounters than we had, and their encounters were more serious. Mary asked Sherpa about the two bear claw marks on her shoulder, of which she was very proud. A few days earlier, she and Crow had made camp in Yosemite Valley during a side trip to see the sights. Following regulations, they had stashed all of their food in a bear canister outside their tent. A bear visited their camp anyway—they could hear it. The animal walked through camp, wandered off, and then returned. On its fourth visit, it tried to take the canister with it.

Crow and Sherpa both started to get out of their sleeping bags to chase the marauder away, but at that instant, the bear slapped the tent on Sherpa’s side, knocking her on top of Crow. The bear’s claws went all the way through the tent fabric and left a deep puncture wound on Sherpa’s shoulder. Then it ran off. Crow applied first aid, and in the morning the two continued with their trip. They hadn’t let Crow’s broken wrist earlier in the trip knock them off the trail—they sure weren’t going to let some little puncture wounds get in the way.

Zero Days

Zero Days