- Home

- Barbara Egbert

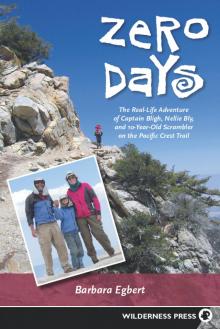

Zero Days Page 17

Zero Days Read online

Page 17

We got our first glimpse of the snow-covered Sierra. It was very magnificent!

Later, as we were getting close to Mt. Whitney, we watched a storm move through the mountains several miles east of us, creating a dramatic landscape that reminded Mary of scenes in The Lord of the Rings. She wrote

Day 53: We had beautiful views. The most spectacular was something I named the Dragon Mountains. The Dragon Mountains were so misty and mysterious. It looked like orcs could pour out any minute! But in front of them were sunny, sandy mountains, the opposite of the ominous, softly lighted mountains.

Months later, I called a halt to a day’s hike a few miles short of our goal because dusk was falling, and in my state of heat-induced exhaustion, I didn’t think I could safely navigate the upcoming rocky tread. We were all plenty tired as we set up camp at a wide spot next to the trail, but Mary was never too tired to appreciate everything she saw. In her journal, she wrote:

Day 108: We saw a sunset, bats, and a crescent moon. The sunset was red, orange, and purple. The moon was beautiful and bright. There were many bats.

Toward the end of our time on the trail came one of those days when I especially appreciated having a child along. Despite the depth of her experience as a backpacker, Mary still had a child’s knack for seeing something ordinary in a new and wonderful way. We were struggling through the snow of Washington’s North Cascades on what I was beginning to regard as a losing effort to get to Canada before we all froze to death. Gary was breaking trail, then came Mary, and I was bringing up the rear, thinking doleful thoughts. Mary pointed out how the little clumps of snow that we dislodged with our boots would roll down the steep slope to our right, pick up speed, and become miniature snowballs, carving erratic channels on their way down. Some would stop fairly quickly, while others would pick up speed and travel surprising distances. Once in a while, Mary would knock off a clump about the same time as I did, and the tiny snowballs would race downslope like competing skiers. Occasionally, one would change course and knock the other off track. This quickly became a little game for us, predicting which snowballs would roll the farthest. I cheered up in spite of myself. Mary’s talent for introducing an element of play into almost any situation made all those miles I used to carry her on my back worthwhile.

CHAPTER 7

PAIN AND SUFFERING

Day 125: Today Dad’s knee hurt him very badly. He fell. We had a heckish time getting water.

—from Scrambler’s journal

THE FIRST INDICATION OF SERIOUS PROBLEMS on the trail came at Olallie Lake in northern Oregon. The best scenery along Oregon’s section of the Pacific Crest Trail is supposed to be in the northern half of the state, where the trail meanders through the Olallie Lake Scenic Area and Mt. Hood National Forest. Guidebooks tout the visual wonders of Mt. Washington, Mt. Jefferson, and Three-Fingered Jack. We had seen nothing of them. Rain had fallen for several days, and clouds and mist obscured our view of everything but the nearest trees. Creek fords had become deeper and colder. Our boots were constantly wet. Concerns about dangerous stream crossings had persuaded us to take a long detour around Russell and Milk creeks, requiring a short but risky road walk. Breaking camp meant packing up under a tarp, a difficult and back-breaking process. Setting up camp meant more of the same.

Hand-numbing cold had replaced northern California’s mind-bending heat. And I mean numb. A few days earlier, I had felt an urgent call of nature as we plodded along through a drizzle. As usual, I told Gary and Mary to go on without me; I would take a quick pee and then catch up. But when I tried to get my pants down, I couldn’t unfasten my belt buckle. It was the kind of buckle where all you have to do is push in from either side to release it. It’s meant to be easy to operate even with mittens on. But I couldn’t do it. My chilled hands refused to cooperate, and Gary and Mary were too far ahead to hear me shout for help. Luckily, I discovered that I had lost so much weight, I no longer needed to open the buckle and unzip—I could just pull my pants down right over my hips, do my business, yank them back up, and catch up with the rest of my family.

On this particular September day—our 138th on the trail—we had experienced not only rain, but snow and sleet as well. The PCT wasn’t so much a trail as a navigable waterway. I half expected to see a flotilla of canoeists paddling by. We tried at first to walk around the worst of the puddles, but eventually we gave up. Our boots and socks weren’t just wet; they were soaked. Saturated. Waterlogged. And that was just within the first mile. We eventually reached a dirt parking lot where we took shelter under the tiny roof of a forlorn outhouse.

Desperate for something to eat, the three of us jammed into an area the size of an old-fashioned phone booth. With our packs and my trekking poles, there wasn’t much room to maneuver. I wriggled out of my pack and attempted to hold it above the wet ground with one hand, while opening the buckles on the pack lid, loosening the drawstring, and rooting around in the food bag with the other. I eventually managed to fish out three energy bars while Gary and Mary tried to grab their water bottles without taking off their ponchos or their packs. Houdini would have found this a challenge. The outhouse hadn’t been cleaned in quite some time, judging from the smell, and after about 10 minutes, Mary announced that she was feeling faint. With some cajoling, Gary convinced her she was OK, only to have me complain a few minutes later that I was about to pass out. I abruptly opened the outhouse door, plunked myself down on the rusty metal lid, and tucked my head between my knees. We had reached a new low.

THIS WASN’T THE FIRST TIME we had experienced physical agony and mental suffering along the PCT. A certain amount of discomfort is inevitable during an effort of this magnitude. We had dealt with blisters and joint pain, heat, cold, rain, and snow. Looking ahead in the trail guides, we had worried about how to deal with dangerous stream crossings and difficult navigation. But so far, we had suffered these discomforts one at a time; it had been the pain or the uncertainty or the weather that had been hard to bear. On this day in central Oregon, they all hit at once. Nonetheless, like every other day on the trail, we had no choice but to continue. The dirt road that led away from our temporary refuge might not see a vehicle for weeks. And that night’s proposed shelter was just a few water-logged miles away.

As we left the outhouse, dusk was falling right along with the rain, and we passed a series of ponds—now overflowing onto the trail—that indicated we were getting close to Olallie Lake Resort, our resupply destination, where we also hoped to get a cabin for the night. Beyond the constant downpour, it was cold and we were very tired. We found the store where rooms could be reserved just before the clerk locked up, and just in time to grab the last available housing. I imagined we could soon relax in a “charming lakeside cabin,” as advertised in the resort’s website, with light and warmth and comfort. Don’t get me wrong, I was glad to have any kind of roof over my head at that point. But the accommodations fell somewhat short of the picture in my mind. Our cottage reminded me of the cabin in which author Jack London spent the winter in the Alaskan backcountry: small, dark, and cold. The lighting consisted of a pair of dim gas lamps that together produced about as much illumination as one votive candle. There was no bathroom—the outhouse was about 50 yards away—and for water, there was an outdoor tap. Fortunately, there was firewood. I’m a past master at starting a fire in a wood stove, having relied on one for six years in northern Nevada’s Washoe Valley, and I soon had a blaze going. We pushed the two benches close to the stove and gathered around it, arranging boots, socks, ponchos, jackets, and most of the rest of our belongings around the fire to dry them out.

We were just starting to get warm enough to relax when there came a knock on the door, and out of the cold, rain, and wind, a section hiker appeared. With no cabins left, Hiker 816 had come to us to seek refuge from the storm. We took him in, of course, and he turned out to be a very considerate house guest. He settled down in the corner nearest the door, offered intelligent conversation, and insisted on sharing the co

st of the crowded, smoky lodging. But even his cheerful endurance couldn’t mask the fact that we were huddled around a wood stove in a tiny, mouse-infested cabin, while outside, the terrain through which we would soon have to travel became colder and more sodden with each passing minute. And the rain just kept falling.

It’s hard to explain to non-backpackers why we hate rain the way we do. As we learned in Oregon, of all possible weather conditions, rain creates the most sheer wretchedness, especially in cold weather, and also the most petty annoyances.

A rainy day begins with the unpleasant task of breaking camp without getting everything wet. Imagine us in our little home away from home, our 6-by-8-foot Eureka Zeus tent. There’s enough room for the three of us to lie comfortably abreast, and there’s a little extra room at the head end—plenty of space normally, but cramped if we have to pile our packs inside, instead of keeping them under the vestibule at the tent’s entrance. Besides the empty packs and gear at the head end, we must stack our bear-proof Ursacks at the foot end, where they provide a waterproof barrier between our sleeping bags and the tent wall. The remaining space comprises our living, dining, and bedrooms. At breakfast, we sit up, keeping as much of our bodies inside our sleeping bags as possible, while we eat Pop-Tarts, using Ziploc bags for placemats to catch the crumbs. We then take our two pack towels and wipe the frost and condensation off the inside of the tent, so we don’t rub against it and get our clothes and gear soaked.

Getting dressed is awkward, especially for me, for two reasons: First, I sleep in the middle, and anytime I stick out a foot or an elbow, it’s likely to connect with a member of the family; and second, my knees are stiff and don’t want to bend. Eventually, we’re suitably attired for the weather and it’s time to stuff our sleeping bags and roll up our sleeping pads. There’s just enough head room for sitting up, but none for standing, and no room to maneuver. So in order to pack, we must dodge around each other to grab the clothing and gear that have become scattered all around the tent. Done with the easy parts, we put on our rain ponchos (still damp from the previous day), go outside, and take down the tent while bending over, underneath the rain fly, in an effort to keep the tent and our packs dry. Finally, we put on our packs, drape our rain ponchos over them and us, and start walking. Sometime during this process, we each in turn answer nature’s call and try to keep our skin and clothing from getting soaked in the process.

That gets us out of camp. Walking in a light rain on a wide, well-drained trail isn’t so bad. Soon, however, the rain comes down harder, the trail becomes muddy, the rocky portions get slick, and our boots and socks become soaked. Invariably on rainy days, the trail narrows and we have to push through the wet leaves of overgrown brush, which deposits water on our pants. Rain ponchos don’t do much to keep our pants dry—if we wear them so that they hang down enough to protect our pants, they catch on twigs and trip us; instead, we remove the zip-off legs and just put up with the wet, slimy, and occasionally thorny branches slapping our legs. Of course, then our socks and boots get even wetter. Pretty soon, we’re hungry, but there’s no shelter, so we wait until the rain lessens before stopping to grab some candy bars out of the food bag. But as soon as we sit down and unwrap our bars, the rain picks up and we have to move again, trying to shove a few bites into our mouths as we walk.

When we find a place to camp, we have to set up the tent and get everything inside it while keeping our gear dry—almost impossible in a heavy rain. Gary has to filter water, regardless of the weather. At least I don’t have to cook in the rain; when the weather is bad enough, we eat energy bars or Pop-Tarts in the tent and skip the hot meal. But that still means stooping under the rain fly, getting out of our wet ponchos and boots and damp clothes, and trying to get warm without getting water on or in our sleeping bags.

For Mary, rain was the worst part of the PCT, and the “Olallie day,” as it became known in our family, epitomized our misery. “The trail was a river, ankle deep,” Mary recalls. “There were waterfalls on the trail, and then we went over the pass (it was snowing), and after that, we went through territory with lots of pretty little ponds—supposedly—but they formed one continuous lake about 2 feet deep, and it extended over the trail. Mom and Dad waded, but I tried to hop across. It was really awful.”

To say Mary hates wet boots is an understatement along the lines of saying that she finds mosquitoes slightly annoying. By the time she crossed Oregon and Washington, she developed such an aversion to cold, wet boots, that even now she’ll do anything to avoid hiking in the rain.

For Gary and me, rain wasn’t the biggest challenge. Our primary trail nemeses came from our own bodies. While I temporarily lost my tendency for lower back pain and my sensitivity to poison oak while hiking the PCT, I developed new, unexpected maladies. During July, I was able to work through fairly severe pain in my right leg in the southern Sierra, thanks to Gary and Mary taking some of my pack weight, and thanks to my mule-headed determination to avoid seeking medical advice. But the blisters were another story.

My problems began at the border. Some thru-hikers boast about how long it takes before they develop their first blisters—or even that they never endure any at all. They chide those of us (mostly older) hikers who develop blisters or other foot problems early on. But I began the trail already afflicted with blisters. I had acquired them during a weekend training hike a few weeks before beginning the PCT, and they hadn’t had time to heal. While planning our hike, I had expected that most foot problems would occur early on, and then they would clear up, leaving me with tougher feet for the duration of the hike. Foolish me. I started out with this big, painful blister under the ball of my right foot—and not only did it fail to clear up, but I developed others as well. After a few weeks, I noticed that I seemed to have a lump underneath the spot between my big toe and the one next to it, on my right foot. I kept shaking out my boot to get rid of whatever was causing the lump. A rock? A twig? Eventually, I looked at the foot itself and discovered the source of the discomfort: an ugly, pink sore between the two toes. Just looking at it made me queasy.

Basically, my feet hurt all the time. Remember that scene in the movie version of The Da Vinci Code, where Silas removes his “cilice,” that barbed thing he wraps around his thigh for some occasional mortification of the flesh? While everyone else in the theater was going, “Eeeuugghhh!!!” I sat there unmoved. He could take the thing off any time he wanted. I couldn’t very well take my feet off.

When Gary began the PCT, he also had blisters on both feet, which he had to attend to every day. Unlike me, Gary really is a stoic. So when the pain was severe enough that he was complaining about it after only a week, I knew these were no ordinary blisters.

Gary had been experimenting with different footwear right up until we started our PCT hike. The boots were no problem, but he was still trying to find just the right inserts. During a training trip just a couple weeks before we started, Gary tried out a different pair of inserts. They fit badly and pinched his heels, so he started out at the Mexican border with a blood blister on one foot and a cluster of ordinary blisters on the other. Hot weather and 20-mile days didn’t help. One day, Gary had run through a burned-over area to catch up with Mary and me after taking some photos. We took a break, and after 45 minutes on the trail, his foot pain failed to dissipate as usual. After an hour and a half, his feet still hurt. When we finally stopped, Gary took off the bandages and discovered that blisters had bubbled up under his calluses, painfully pushing up the dead skin and causing more irritation. The blisters were too deep to pop, so Gary took a knife and trimmed off the calluses before lancing the blisters. We called it the “Christmas Turkey Blister” because the way he sliced off the skin in layers reminded Mary of carving slices off the turkey at Christmas.

Mary’s feet hurt occasionally in the first few months, but in northern California she developed cracks in the skin where the toes meet the foot. Ordinary first aid didn’t cure them, so Gary began applying a product called New

Skin. Mary remembers very well the burning sensation from New Skin being applied to the “horrible open sores” on her toes. They did clear up, eventually.

Strangely, it wasn’t steady walking that hurt the worst; it was the stopping and starting. During the first couple weeks, Gary would call a break every 60 to 90 minutes. That was as long as Mary and I could tote full packs in the desert heat. We’d sit down, eat and drink for 15 or 20 minutes, and then pack up and get moving. There would be this excruciating period during which our feet screamed for relief. Then they’d get a little bit numb and walking was merely unpleasant.

As we became stronger, we were able to walk longer between breaks, which meant we could not only cover more ground, but suffer a little bit less as well. While our legs and lungs got stronger and healthier every day, our feet stubbornly refused to do the same. After a few weeks, Gary and I had so much moleskin and bandages on our feet, we could hardly see any skin. At first, Gary took care of my feet every morning in the tent, and then his own. Eventually, I learned to be my own podiatrist. Gary insisted on a high level of cleanliness for foot treatments: alcohol wipes, a clean needle for lancing blisters, and large quantities of triple antibiotic ointment. Thanks to that, we avoided infections, despite the fact that our feet were filthy much of the time.

We had problems above the ankles as well. An anti-inflammatory medicine I was taking for my knees at the beginning of the trip made me extra sensitive to sunlight, and after a few days, I developed a severe rash on both legs. It looked and felt like a second-degree burn—red, bumpy, and painful. I had to quit taking the medicine and wear long pants until the rash cleared up. I’ve had chronic bursitis in my hips for years—ever since I took up backpacking, in fact—and my hips ached many nights while I tried to sleep. Worse were my knees. Before we started hiking, I went through six months of physical therapy for those wretched joints, but within days they were aching again. They also kept me awake many nights. Trekking poles helped, but not enough.

Zero Days

Zero Days