- Home

- Barbara Egbert

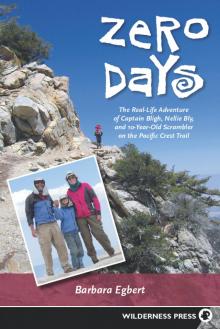

Zero Days Page 9

Zero Days Read online

Page 9

I admired his choice of trail name: Without rudeness, it expressed his preference for solitude. I have since wondered if his Appalachian Trail experience influenced his choice. It’s fairly easy to walk alone on the PCT, especially if you start in early April, as he did. But on the AT, there’s such a crowd of aspiring thru-hikers (upwards of 2,500 each year) and so many others hiking smaller sections that solitude is difficult to come by, except during the most difficult and remote parts of the trail. Or perhaps he was a fan of Henry David Thoreau: “He who walks alone, waits for no-one.”

WOMEN ON TOP is a group of friends who gather annually for a weekend hiking trip. When we met them, they had kept the tradition going for 14 years. There are six or eight core members, mostly living in the Sacramento area, plus a fluid collection of friends who join outings occasionally. About eight of them were sitting in the Sierra Club’s Peter Grubb hut near Truckee, California, one warm evening in July, sipping wine and speculating about the people who had signed the trail register. Who are these thru-hikers, they mused, and what kind of people would spend five or six months carrying heavy packs up and down mountains, while fighting snow drifts, heat stroke and hungry bears? At that very moment, the door opened and in walked my family, right on cue. We were the grungiest hikers they had ever met, and they were just delighted. They treated us like celebrities, gave us food and drink, asked lots of questions, let us cook in the hut, and persuaded us to sleep in the loft (they had tents set up outside). In the morning, there was more conversation, hike-related and otherwise, and we separated with great feelings of amicability, as they departed for a morning hike and afternoon swim, and we started out on an 18-mile day in the intense heat of the northern California summer.

ZEKE told us a lot about himself after we met him in mid-May. The problem was, we didn’t know if we could believe any of it. Zeke is one of those trail names that shows up every now and then, so don’t assume our Zeke is your Zeke. Anyway, our Zeke was staying at a supposedly hiker-friendly establishment on Highway 138, where the business owner was reportedly trying to provide water and a place to sleep for thru-hikers. But the place felt strange, and the people working there even stranger. In fact, it appeared to us that thru-hikers were welcome only if they were willing to provide free labor on the half-finished building where Zeke had been sleeping. We left quickly, not even taking advantage of the water in a garden hose by the fence, and took a 1-mile detour to the country store.

After that, we stretched our legs along the California aqueduct for several miles, finally making a dry camp among the Joshua trees alongside the buried waterway. Zeke caught up with us the next morning, having decided he’d spent enough time off the trail. He walked with us for only a few miles, to the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power spigot in Cottonwood Creek, but during that time he just about talked Gary’s ear off. If he had really done all those important things for the government and the military, then Zeke was quite a guy. So why did we get the feeling that he was making most of it up, and that if we stuck around with him long enough, he’d hit us up for a loan? And if he were such an accomplished hiker, why couldn’t he keep up with a 10-year-old going uphill? We were glad when he decided to camp for the day in the shade of a bridge near the spigot, while we continued on. The next time we saw Zeke was at Kennedy Meadows, where he got my brother to give him a ride to Lone Pine, since George was taking the rest of us to Carson City anyway. We’ve always wondered how he managed to catch up, speculating that he engaged in more than a little hitchhiking to do so.

Despite our misgivings, I feel a certain fondness for Zeke. He fit a particular stereotype of the long-distance backpacker popularly known as “hiker trash” and, as such, filled an important role in our trail experience. “Hiker trash” is a phrase that’s used rather loosely, but generally describes people who have made long-distance backpacking their lifestyle of choice, and who only take jobs (or arrange slightly bogus “fund-raisers”) when it’s time to earn the money to return to their preferred free-ranging existence. Philosophically, they’re cousins of the ski bums hanging out at Sierra resorts and the rock rats who spend their summers bending the rules at Yosemite’s Camp 4. But, as is the case with those other targets of ordinary civilization’s scorn, “hiker trash” is too broad a description for people who discover that their psyches are more suitable to the freedom, dangers, and privations of the long trail than to the comforts, restrictions, and constant petty hassles of the civilized life that the rest of us pursue.

Perhaps “hiker trash” as a personal description should be put to rest. Or maybe a new definition is in order, such as the one trail angel Jeff Saufley came up with when he looked at the dumpster he’d put next to his house in Agua Dulce in expectation of the late-spring onslaught of thru-hikers. Scanning the contents of the bin—the empty food wrappers, used Pringles containers, and worn-out socks—he remarked, “It gives a whole new meaning to the words ‘hiker trash.’”

CHAPTER 4

TRAIL ANGELS AND DEMONS

Day 95: We walked 10 miles. We went to the Heitmans’. Georgi and Dennis Heitman were very nice. I learned how to spin. I played with their new kitten, Scamper, and soaked in their hot tub.

—from Scrambler’s journal

ANDREA DINSMORE AND I couldn’t have less in common. She’s a retired truck driver; I’m a newspaper copy editor. She’s outgoing and enthusiastic; I’m introverted and restrained, like one of Garrison Keillor’s Norwegian bachelor farmers. She was a heavy smoker when we first met, and swore like a character in a Carl Hiaasen novel; I’ve never smoked and, as I’ve mentioned, strong language doesn’t come easily to me. We hit it off immediately.

Andrea, who is a couple years older than me, and her husband, Jerry, a few years older than her, are widely known as the trail angels of the far north. In the backpacking community, trail angels are the people who make a hobby of helping hikers by providing water caches, letting people stay with them, giving rides, cooking meals, accepting resupply boxes, and otherwise making backpackers’ lives easier. But the angelic circle is much larger than that. We were helped by an entire host of trail angels, before and during our PCT experience, from the on-trail angels, like the Dinsmores; to the off-trail angels, like my little sister, who mailed all our resupply boxes; to the accidental angels who were in just the right place at the right time to help us in some way. We also met a handful of memorable characters—and just a few demons.

The Dinsmores’ activities during the hiking season exemplify how the serious on-trail angels do their thing. Jerry and Andrea live west of Stevens Pass, where the PCT crosses Washington’s Highway 2. A typical hiker might arrive after dark and, having been provided with Andrea’s phone number at an earlier town stop, pause at the pay phone in front of the highway maintenance shed and call that number. Since this is Washington in autumn, it’s not only dark, but cold and drizzly as well. While daytime arrivals hitchhike to Skykomish and call from town, backpackers who arrive at the pass after dark can call and ask for a ride from there. The voice on the other end of the line is so cheerful, it’s downright surreal. In a few minutes, a pickup truck arrives, with Andrea and a tiny dog in the front seat, and room under the camper shell for a backpack and trekking poles. And in a few minutes, the hiker, his faith in human nature restored, has been whisked away to Dinsmores’ River Haven on the banks of the Tye River, where the Cokes are always cold and the showers hot, and where Andrea’s parrot, a Congo African grey named Topper, swears like President Nixon on a particularly bad day.

I stayed with the Dinsmores nearly a week, first plotting an alternate course around the storm damage through Section K’s Glacier Peak Wilderness, and then shuttling Gary and Mary back and forth for three days between the alternate route and the travel trailer we three slept in. At this time, I was off the trail recovering from injuries and was acting as a mobile trail angel myself, so that my husband and daughter would have a better chance of finishing. I arrived at the Dinsmores a day or two before Scrambler

and Captain Bligh did and was sitting at the little kitchen table one evening reading a Seattle newspaper when I heard someone upstairs cussing vigorously. “Blanketty-blank-blank you, you blanking blank-blank, Jerry!’’ Omigod, I thought, they’re having a fight and I’m an unwilling eavesdropper. And then I remembered I had just seen Jerry in the living room, smoking a cigar, and watching television. I crept up the spiral staircase for a look-see. It was the parrot, Andrea explained from her second-floor desk. A couple weeks earlier, she had stepped a little too close to the bird’s spacious cage, and the feathered ingrate had bitten her on the lip. Andrea had reached through the bars, grabbed the offensive fowl by the throat, and hissed, “You (fill in the blanks with a long string of epithets culled from a 25-year truck-driving career) bird, I’ll throttle you!” The parrot wasn’t particularly good at memorizing phrases, but it picked this one up perfectly, just as when a parent lets slip an unfortunate remark in front of a small child. Over the next several days, Topper gradually shortened the string, but improved upon it by adding “Jerry” to the end of it. And the result is what I overheard from the Dinsmores’ kitchen.

Topper could memorize more than just cuss words. He also learned a phrase that struck fear into our hearts as we headed into the North Cascades. “Snow, snow, snow,” he would recite in a rising tone, and then add with great emphasis, “Scary! Scary!” Andrea monitored the TV weather reports as well as the National Weather Service website, and her avian Cassandra must have picked up on the emotion in our voices when we discussed the forecast.

We learned about the Dinsmores by lucky happenstance. While hiking north through Washington state without me, Captain Bligh and Scrambler met a couple heading south who gave them Andrea’s contact information, which they passed on to me. I then phoned Andrea from Snoqualmie when it was time for me to move my base of operations northward. But it’s no accident that they take in thru-hikers. The quiet life of retirement isn’t for them, not when there are hikers out there to share their adventures and tell their life stories. Andrea gave me the most concise explanation I’ve ever heard as to why so many people, who will themselves never walk a long trail, are so eager to help. “They need us!” she exclaimed, opening her arms wide as though to enfold all those hapless hikers who, having experienced Washington’s bad weather, voracious mosquitoes, and difficult resupply logistics, needed a warm heart and a warm room off the trail. A couple years after we stayed with the Dinsmores, an electrical short caused a fire that severely damaged their home during March. A house fire is a traumatic event, but Andrea’s primary concern even then was the welfare of the thru-hikers. In her messages, it seemed her biggest regret was the loss of her hiker boxes with food and spare gear. And one of her happiest moments came in June when the first thru-hiker resupply box arrived in the mail, proof that she was again in the business of being a trail angel, even if she and Jerry were still living in their motorhome next to the damaged house.

Contrary to how it might seem, given how well the trail angel network runs, there is no official system. People become trail angels by chance. There’s no individual or organization that oversees their activities or keeps track of who’s doing what in any particular year. The trail angels who regularly let people stay with them advertise their charitableness in various ways, from word of mouth to sophisticated websites. There are so few of them that there is no typical level of involvement. They became interested in different ways, they participate in the trail community at various levels, and they discover individual solutions to the problems of incorporating their trail angeling into their personal, professional, and financial lives.

The Dinsmores became trail angels in 2003. Jerry had dropped by the Skykomish post office after meeting friends for coffee one morning. The four men he talked to at the post office looked like homeless people at first, but when he realized they were thru-hikers looking for a place to clean up and sleep, Jerry brought them home. Andrea remembers meeting them for the first time. “All it took was chatting with them for a bit to figure out that what they looked like, and who they really were, was night and day,” she recalls. Andrea and Jerry took in six or eight more hikers that year who found their way to Skykomish, about 15 miles off the trail, in search of shelter and laundry facilities.

The next year, Gary, Mary, and I were among the swarm that suddenly discovered the River Haven. “Had no idea what we were getting into,” Andrea says, recalling their start. “But, we love it.” The Dinsmores now ask thru-hikers to contribute a small amount toward their lodging, which must be pretty special in the new hiker dormitory that was being constructed in 2007 just for backpackers, complete with bunk beds, TV, phone, internet connection, movies, microwave, and a coffee pot. How to host a couple hundred backpackers over a three- to four-month period without losing all control over one’s own personal life is a problem trail angels solve in a variety of ways. The Dinsmores’ hiker hut is the approach they’ve chosen to have their visitors close, but not constantly underfoot.

As with the Dinsmores, an encounter at the post office led to Georgi and Dennis Heitman becoming trail angels. In 1998, a young lady whom they had known for many years through Georgi’s work with the San Francisco Bay Girl Scout Council asked if she and her new husband could stay overnight at the home the Heitmans had built at Old Station, in northern California’s Shasta County. Melody and Darren were planning to hike the PCT on their honeymoon and knew roughly when they would reach the tiny resort town a few months later. The Heitmans said, sure, come on by. But then Georgi’s mother suffered a massive stroke, and what with the stress of driving several hours to Oakland, California, every other week to help her mother, she forgot about the visit. Luckily, as Georgi was returning home from one of those trips, she stopped by the post office, and, she says, “There they were, waiting for me to pick them up.” They stayed two nights, and before leaving, Melody asked that fateful question: Could they put the Heitmans’ name and phone number in the PCT trail register at the Old Station post office, in case other backpackers needed a trail angel?

They said yes, but for the next several years, only a few hikers called for help. The most they hosted at a time was five. Everything changed in 2004, when, for some unknown reason, more than three dozen hikers stopped by. Now the Heitmans are known well enough that they can expect to host dozens of thru-hikers and section hikers every summer, all based on that one visit. Looking back, Georgi says, “We were clueless, but it’s all right, we love this uproar. It keeps us young, and how else could you get the world to come to you, here in the back of beyond?”

Our visit with the Heitmans was a high point for all of us, but especially for Mary. Dennis had just acquired a new kitten, and Mary got to play with it. Georgi showed Mary how to spin wool on one of the spinning wheels she collects. This extra kindness that many people showed Mary was one of the things that made our trip special. Many people we met seemed to consider it a privilege to do little extras for the little girl on the trail. And Mary responded by eagerly participating in whatever activity arose, from playing with a tiny puppy at the Seiad Valley post office to enjoying an impromptu early birthday party at the Dinsmores, complete with Andrea’s gift of a Barbie doll in an outfit as extravagantly removed from a thru-hiker’s travel-worn garments as it’s possible to get. As word spread ahead of us that we were on the way, we discovered, trail angels would actually look forward to meeting us—and if logistics didn’t allow a visit, they seemed genuinely disappointed. One of these much-anticipated meetings occurred in the southern California town of Agua Dulce.

When PCT hikers hear the words “trail angels,” the names that most often come to mind are Jeff and Donna Saufley. At first, I thought this couple was too good to be true: At their ranch-style home in the desert near Palmdale, they welcome thru-hikers, let them camp, cook, and shower there, and even let them sleep in their mobile home. As if that weren’t enough, the Saufleys also do their laundry, accept their packages, and loan out their car. Too good to be true? For once, I was

wrong. The Saufleys live a few days’ hike from a particularly hot and dry section of trail that backpackers dread. Every year, they welcome hundreds of thru-hikers and section hikers to their home. They do indeed perform an amazing variety of services, while working full time and caring for their two draft horses and half-dozen or so dogs. Most any online trail journal or PCT-linked website tells backpackers everything they need to know about finding and staying at Hiker Heaven. The amazing thing is, everyone who stays there comes to feel in a short time that he or she has formed a personal friendship with the Saufleys. We were fortunate to be ahead of the main wave of hikers when we arrived in early May, and we were among just a handful of people staying there. Donna had heard we were coming and was very eager to meet Scrambler. The two of them became instant friends. But I’ve talked to many other backpackers, and read their journals, and each one felt while staying with the Saufleys that he or she was made to feel special. Jeff and Donna are just plain amazing.

Among the stories trail angels tell about how they came to embrace thru-hikers as a vocation, Jeff and Donna’s is my favorite. Donna starts the story with the exact date: Saturday, May 31, 1997. “What was extremely unusual about that evening was that I was going to be home alone, presumably all night, for the first time in the five years Jeff and I had been married,” she remembers. “My son was with his father, and Jeff was going to an all-night bachelor party.” Donna wasn’t one to sit around alone on a beautiful evening, so she called all her girlfriends. “But it had been some time since I’d talked to them, and they all had husbands or kids or some other reason they couldn’t go out,” she says. “So I struck out. I was bummed, but I figured I’d find something else to do.” She remembered seeing a sign advertising a powwow down at Vasquez Rocks, a large county park characterized by huge sandstone slabs tilted up at an angle of about 50 degrees. The park is named for Tiburcio Vasquez, a 19th century bandit who built up a Robin Hood-type reputation while robbing stagecoaches and rustling livestock. (Scrambler describes the rocks as resembling giant pancakes, made from different recipes—thus the varying colors—and flipped up into the air. By the time we reached the rocks, we were seeing reminders of food almost everywhere.) Other people must see something alien in the rocks, which have provided the backdrop for TV episodes of The Outer Limits and Star Trek, as well as Blazing Saddles and many other movies.

Zero Days

Zero Days