- Home

- Barbara Egbert

Zero Days Page 2

Zero Days Read online

Page 2

—from Scrambler’s journal

JUST NORTH OF KITCHEN CREEK, 30-some trail miles from the Mexican border, the Pacific Crest Trail crosses a clearing near a campground. A small PCT marker guides thru-hikers on their way north; a side trail to the left leads down to a dirt road. As Mary, Gary, and I entered the clearing through tall, fire-scorched brush on a warm April morning, a woman wearing a bright red shirt watched us curiously. She and her husband and their two children—boys about 7 or 8 years old—had walked up the small hill to the trail intersection.

“Hello,” Mary greeted the young mother as we approached. Always friendly, Mary is eager to socialize with everyone she meets. “Hello,” the woman responded. “Where are you going?”

Mary pointed to the trail sign: “We’re hiking the PCT.” The woman had obviously never heard of the PCT, and she looked at me with the quizzical expression of an adult confronted with a completely nonsensical statement from a child. “We’re hiking the Pacific Crest Trail,” Gary explained. “It goes from the Mexican border to Canada, 2,650 miles. We’re on our third day.”

At this point, the woman’s expression changed to something between disbelief and fear. I assured her we were sincere. She looked at her husband and children, then at Gary and me, with our sweaty faces, big packs, and little kid in tow. “You’re kidding,” she said. Then she said it again, “You’re kidding.’’ Finally, she turned to Mary and exclaimed, “You’re not going to let them make you do this, are you?” Mary folded her arms, stuck out her chin, and replied, “They’re not leaving me behind!”

As the magnitude of our endeavor sank in, I could picture what was going through this woman’s mind. A hike of the Pacific Crest Trail is an impressive feat, especially for a child. Beginning in southern California’s Mojave Desert at a modest monument near the wall along the southern border of the United States, the Pacific Crest Trail runs from Mexico to Canada, ending at a matching monument on the northern border, at the edge of British Columbia’s Manning Provincial Park. Along the way, the trail rises and falls through the San Jacinto, San Bernardino, and San Gabriel ranges (and the desert valleys in between) before ascending to the crest of the Sierra Nevada. Its highest point, at 13,180 feet above sea level, is at Forester Pass in the southern Sierra. Continuing north over a succession of lofty mountain passes through Sequoia, Kings Canyon, and Yosemite national parks, the trail takes in views of Lake Tahoe in central California and then winds its way north through the mountains toward Lassen Volcanic National Park in northern California. Following the crest of the Cascade Range, the PCT offers views of Mt. Shasta before continuing into Oregon and Washington on a route punctuated by more volcanoes, including Mt. Jefferson, Mt. Hood, Mt. Adams, the still-smoking Mount St. Helens, and the mighty Mt. Rainier. At the Canadian border, as if ushering jubilant hikers back to civilization, there is a broad, 7-mile trail to the nearest paved road.

The PCT zigzags along ridgelines, meanders through public property, and follows wandering rights-of-way across private lands. The trail is more than twice the length of the highways that travel the same route from south to north; indeed, if you wanted to drive a distance equivalent to the trail, you would have to take your car from Los Angeles to Baltimore. Because of its length, PCT thru-hikers typically allow five to six months to hike the entire distance. Our own PCT adventure lasted from April 8 to October 25, 2004.

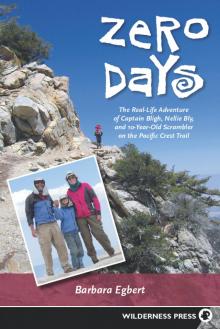

It’s not surprising that most people who encountered our threesome reacted with disbelief. Even if they had heard of the trail—and many had not—it’s rare to see a pair of 50-something parents and their 10-year-old cheerily saddled up with big packs for the trip. The people least likely to believe we could do it—much less would want to do it—were adults engaged in a weekend camping trip, complete with RV, generator, running water, and television set. It’s hard enough explaining to sympathetic friends and relatives why we would want to spend an extended vacation lugging heavy loads up steep hills, sleeping on the ground, and digging holes for trailside latrines. But parents whose children have to be cajoled to move more than a few feet away from their video games cannot imagine a 10-year-old girl who can walk 20 miles a day with a full pack, and get into camp still capable of climbing trees and making up games with twigs and pinecones.

We found ourselves constantly responding to the kinds of questions that dayhikers and car campers are prone to ask upon meeting a trio of hard-muscled, razor-thin, scruffy-looking hikers intent on racking up a 20-mile day: How do you get food? How often do you take a shower? How come your daughter’s not in school? But the biggest question everyone asks, which is even more important than how much weight has been lost and how many bears have been seen: Why are you doing this?

THE STORY OF WHY we attempted to hike the Pacific Crest Trail as a family—and in the process gave Mary an opportunity to become the youngest person to finish—begins even before Gary and I met. While I spent my childhood exploring the high desert and lonely mountains of east-central Nevada, Gary was rambling around rural Maryland, 2,000 miles to the east. We both grew up comfortable in the wilderness and felt a strong need to escape into it frequently. We were in our 30s when we met in the spring of 1988. I was living in Baltimore doing a year of volunteer work, and because I had no car, I jumped at a friend’s offer to join a hike and get out of the hot, humid city. That’s where I met Gary, along the banks of the Gunpowder River. Soon, he invited me on our first date; rock climbing at Annapolis Rocks, along the Appalachian Trail in Maryland, I learned how to belay with no difficulty, but when it was time for me to rope up and ascend a fairly easy climb, I froze. I was maybe 6 feet off the ground and I panicked. Couldn’t move up, down, or sideways. Gary had to coax me down like a police negotiator talking a desperate stockbroker off a 20th-story ledge. To my surprise, Gary invited me on a second date, my very first backpacking experience. We hiked into Virginia’s Shenandoah National Park on a Friday evening, and I thought I would collapse from the heat and humidity. But otherwise it was wonderful, and I discovered that I loved backpacking as a novice just as much as Gary did, with his 20 years of experience.

Gary drove out to California the next year so that we could get married. The bridegroom’s present to the bride: Hi-Tec hiking boots (still my favorite brand) and a pair of convertible pants—the kind with zippers around the legs that allow you to change them from trousers to shorts without taking off your boots. We took care of the important stuff first—a pre-nuptial trip to the Grand Canyon—and after that dealt with such minor details as meeting with the minister, purchasing the wedding rings, and inviting guests to our outdoor ceremony.

By the time Mary was born four years later, Gary and I were a bona fide backpacking couple, and we knew we would include Mary in the backcountry outings that were our chief form of recreation. She was only two months old on the first trip, to Manzanita Point in Henry Coe State Park, southeast of San Jose. It was a sunny January day, and I carried Mary in a sling, while Gary heaved about 90 pounds—including Mary’s infant car seat—the few miles from park headquarters to our campsite. Except for Gary’s enormous load, it was an easy trip with mild weather, only a few miles to walk, and a spacious campsite with a picnic table. I was breast-feeding and we used disposable diapers, so feeding and diapering were simple. We divided tasks so that Gary took care of our camping chores, setting up the tent, arranging the bedding, and making dinner, while I looked after Mary’s needs.

Nonetheless, I was nervous those first few trips taking our baby into the wilderness. I couldn’t sleep because I was so worried about how Mary would fare on those chilly nights in the tent. Infants can’t regulate their body temperatures as well as adults, and they don’t wake up and cry when they get cold, as older children will. They can quietly slip into hypothermia. I arranged Mary as warmly and comfortably as possible in the car seat, inside our four-person dome tent. Then I crawled into my own sleeping bag next to her. I would check her every few minutes to make sure she was warm enough. If I didn’t think she was, I’d take her into

my bag to warm up. I didn’t dare fall asleep, for fear of rolling over on her. Every couple hours, she would cry and I would nurse her.

Some of the adjustments we made for family backpacking trips would occur to any experienced parent: Allow extra time for camp chores, and venture out only during good weather. But I quickly learned other tricks, like trying to schedule our trips during a full moon, which made it easier to discern the outlines of baby, blankets, and diaper bag in our dark tent. Some things we learned the hard way. During a particularly inconvenient phase in our backpacking history, Mary was throwing up—a lot—and it was then that we discovered the importance of sealing everything that is wet, or could possibly get wet, inside two Ziploc bags. I even got the hang of breast-feeding while walking. This was an invention born of necessity: We were hiking near our home to a backpackers’ site in the Sunol Regional Wilderness, and a steep hill lay ahead of us, when Mary made it clear she needed to be fed. But if I stopped for 20 or 30 minutes, darkness would overtake us before we reached the top. I stopped long enough to let her latch on, arranged the sling around her securely, and carefully resumed walking. To my surprise, the motion didn’t bother her, and we reached our destination in plenty of time, with a happy, well-fed baby to boot.

At six months, Mary moved into a Tough Traveler “Stallion” model baby backpack, with all the options: a rain hood with a clear plastic window, side pockets, and an extra clip-on pouch. Mary frequently fell asleep in the backpack. Her little head would rest against the pack’s coarsely textured fabric, and she would develop a rash there. So we padded those parts with flannel from an old nightgown. We also made a two-part rain cover out of waterproof, ripstop nylon, with Velcro to hold the two parts together. On clear days, we used diaper pins to clip together receiving blankets or old crib sheets to ward off the sun. I also bought a little round rearview mirror from an auto-supply store that I used to check on Mary when she was on my back. You wouldn’t think a small child could get into trouble in a baby backpack, but during a trip to northern California’s Lost Coast, she managed to pull some leaves off a tree and stuff them in her mouth. Another time, while we were returning from the summit of Utah’s highest mountain, 13,528-foot King’s Peak, she somehow managed to squirm around until she was riding sidesaddle.

By the time Mary was 1 year old, we had taken her backpacking six times, and to celebrate her first birthday, we took her on a trip down the New Hance Trail off the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. Each year, we kept hiking and backpacking as a family, tailoring the trips to Mary’s needs and abilities, but always challenging ourselves to do more. Back then, there were few books on backpacking with children, and the few in print suggested that it just couldn’t be done at certain ages. We never found that age. If Mary couldn’t walk the entire distance, I would carry her part of the way. If she wanted to walk but was getting tired, I would entertain her with endless stories to keep her mind off her problems. On our trip to the Grand Canyon, we hit bad weather as we were hiking out. We had swathed the pack with our home-sewn rain cover, but this meant Mary couldn’t see out the plastic window in the hood. And she got bored. I sang. I told stories. And then Gary hit on the perfect boredom reliever: raspberry sounds. One of us would make a loud noise, blowing out with our lips flapping, holding it as long as we could, and then the next would try to top it. This got us all laughing, and eventually we made it back to the trailhead.

As Mary got older, we discovered that dehydration was the surest source of trouble, and that crankiness was the surest sign of dehydration. Whenever Mary complained about the heat or the distance, or sat down in the trail and refused to move, we’d have her drink a cup of water. If it was late in the day and Mary was getting too cold or sleepy, we’d start looking for a place to set up camp. Just knowing she wouldn’t be forced beyond her limits, or criticized for weakness, helped Mary enjoy backpacking when she was small. By the time Mary was in kindergarten, she could easily hike 10 or 12 miles at a stretch, climb Mission Peak (the 2,517-foot hill that dominates the skyline around our home in Sunol), and help with camp chores.

Although Mary, Gary, and I don’t remember exactly whose idea it was to hike the Pacific Crest Trail as a family, I can trace the genesis of the plan to 1999, when we hiked the 76-mile portion of the PCT that runs from Tuolumne Meadows in Yosemite National Park to Sonora Pass. That ambitious expedition was the watershed trip for everything that followed. Mary was five-and-a-half years old when we began planning. Initially, we decided we would take her out of first grade for a week in October and hike what is known as Section J of the Pacific Crest Trail in the central Sierra Nevada. (The PCT is divided into sections of 38 miles to 176 miles, labeled alphabetically from south to north. All of California is divided into sections A through R, and then the alphabet starts over again. Oregon and Washington are divided into sections A through L.) On the map, the 60-mile stretch from Sonora Pass north to Carson Pass looked rugged but not too challenging. Two weeks before our start date, however, I suddenly remembered something I had almost forgotten after 10 years of living in the heavily populated San Francisco Bay Area: hunting season. Gary and I might have risked it anyway, with the help of matching Day-Glo orange vests, but we weren’t about to put Mary in harm’s way. She was a strong hiker, but hardly bulletproof. We hastily rewrote our plans so that we would go south from Sonora Pass instead of north, thus spending most of our trip on National Park Service land, where hunting is prohibited. This change from Section J to Section I also meant a longer and more difficult trip. Gary arranged to change our permit, and I talked my older sister, Carol, into picking us up in Yosemite.

When we reached Smedberg Lake in the Yosemite backcountry’s perfect alpine setting of granite and evergreens, we had been out five days and were 50 miles into the trip. That day, we had walked 12 miles with a total elevation gain of 3,500 feet. Mary was happy as a lark. While Gary filtered water and I set up the tent, she took my bandanna down to the edge of the water and “washed” it over and over. Mary had been in particularly fine form that day, leading us up the initial 1,000-foot hill to Seavey Pass, down 1,590 feet to Benson Lake, and then up 2,500 feet before dropping down to Smedberg Lake.

That’s when we realized that Mary had it in her to tackle a really long hike. This particular section of the PCT is one of the most remote parts of the entire route. The trail doesn’t cross any roads, paved or dirt, for the entire distance. If one of us had suffered sickness, injury, or snakebite, we could have been as many as 38 miles from a road. Most of the eight days we were on the trail, we saw nobody, so we were completely on our own. As it turned out, the Section I trip was a tremendous experience, but not a perfect one. In fact, several things went wrong. What was so encouraging was that we were able to deal with them.

The problems started on our first day. Leaving Sonora Pass in late morning, we ran into trouble after a few miles when the trail headed straight into a steep snowfield that looked too dangerous to climb. We followed footsteps off to the right, marked by rock cairns, but we still ended up on a precarious, unstable slope. We spent a lot of time working our way down through the shattered rock. Mary took a fall and Gary caught her just in time to avoid injury. This delayed us to the point that we were 3 miles away from our intended campsite as darkness fell. We were all very tired, and we had enough water to get through the night, so we set up the tent on the first flat space we found. The next day, we easily made up the 3 miles and got to Lake Harriet by dusk.

Second day, second problem. About half of the rechargeable batteries that should have been enough for the entire trip turned out to be duds. Most backpackers are early risers, but not us. We like to get up in full daylight, hike until dusk, and then set up camp by headlamp. But now we had to change our habits, getting up at the icy crack of dawn each morning and hiking quickly to take advantage of all the light that an October day holds. We wanted to be in bed, not just in camp, by full dark each evening.

Third day, third problem. When we left our campsite at Lake Ha

rriet, we headed up the obvious trail, only to arrive at Cora Lake, most definitely not where we wanted to be. I was tempted to try to cut cross-country at this point, rather than backtracking and wasting all that time and effort. I stared off across the trees, in the general direction of where we should have been, and asked Gary if we could go that way. His response: Definitely not. Cutting cross-country, he explained, sounds simple but is usually a mistake. Unless we could see our goal, plus an easy route to it, we’d be better off going back to our campsite and starting over. Otherwise, we’d probably get off course, or find our route blocked by a drop-off or impassable thickets.

Gary and I are devoted readers of news articles about people who come to grief in the backcountry. Trying to make up for a mistake by cutting cross-country instead of backtracking ranks high on the list of how hikers get into serious—and sometimes fatal—trouble. A few years after our Section I trip, an experienced outdoorsman decided to take a shortcut through California’s Big Sur wilderness in order to shorten his planned two-week, solo backpacking trip. He ended up stranded at the top of a 100-foot waterfall. Fortunately for him, campers below heard him yelling and got help. He had to be plucked from the inaccessible terrain by helicopter. A year earlier, another experienced hiker found himself off the trail in the Sierra Nevada’s Stanislaus National Forest. Rather than retrace his steps, he looked on the map for a shortcut, and thought he had found one in the shape of a dry streambed. The streambed was so rugged and steep, he eventually fell, ending up too badly injured to walk away. He staggered out days later. Gary had a simple rule to follow whenever we were unsure of where we were, whether on trail or off: Go back to where we were certain of our location, and then decide what to do. So it was back to Lake Harriet.

The fourth and fifth days brought only minor problems, like snow and cold. But on one particular day after we were halfway through, we couldn’t seem to get along with each other. At home, we simply would have avoided each other for a while. Unfortunately, this is not a solution in the backcountry. The interactions among groups of people who tackle stressful activities such as long backpacking trips, big wall climbs, and mountaineering expeditions are pretty intense. The stresses can bring people closer together as they learn to value each other’s strengths while becoming more tolerant of each other’s weaknesses. But it’s just as likely—probably more so—that the stresses will tear a group apart, or weaken it to the point that it doesn’t function adequately. We heard tales about couples who broke up on the trail, or even after finishing.

Zero Days

Zero Days