- Home

- Barbara Egbert

Zero Days Page 3

Zero Days Read online

Page 3

On our seventh day, when we left our frosty campsite at Miller Lake (at 9,550 feet above sea level) and headed for Glen Aulin High Camp, Mary and I were heading down a hill in thick woods a couple hundred feet ahead of Gary. Instead of focusing on the route, I had my mind on my grievances with my husband. I followed what I thought was the main trail, heading off to the right into a meadow. Gary spotted the correct trail, heard our voices, and realized we had gone the wrong way. He shouted for us to stop and to head back toward him. If we had been much farther apart, we might have gone our separate ways for an hour before realizing our mistake. As it was, we all stayed together (however unhappily) until we reached Glen Aulin.

Perhaps what truly foreshadowed our future PCT expedition was the particular stuffed animal Mary had set aside for this trip. We always allowed Mary to bring one stuffed animal on backpacking expeditions, and making the choice was a big deal for her. For this trip, Mary had originally selected a little stuffed porcupine. However, when we arrived at my father’s house in Minden, Nevada, to spend the night before starting, she discovered that my cousin’s son, Andrew, had left her a little stuffed Chihuahua that he had won a few days earlier at the Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk. Mary named it “Puffy” and immediately fell madly in love with it. When Carol dropped us off at Sonora Pass next morning, we learned that Mary had brought Puffy along, and wanted to bring both stuffed animals on the trip. At this age, she didn’t carry anything on backpacking trips, and Gary and I refused to add any more weight or bulk to our well-stuffed packs. This nearly precipitated a major argument just as we were ready to begin walking. At the last minute, Mary agreed to leave the porcupine behind and take only the Chihuahua.

Eight days later, we met my sister, Carol, and her husband, George, in Tuolumne Meadows at the end of our trip. As they walked down the trail to greet us, Carol whispered to George, “Get it out of your pocket.” George pulled out the porcupine and, with a shriek of joy, Mary rushed down the trail to retrieve her little friend. Two years later, it was again Puffy who got to accompany Mary on a big trip, the 165-mile Tahoe Rim Trail (by this point, Mary carried a full pack, including her “animal friend“). But in 2004, the little porcupine finally got his chance. Mary gave him his own trail name, “Cactus,” and carried him on the PCT.

With Section I successfully completed, we began seriously considering a PCT thru-hike. Both Gary and Mary insist it was my idea. (I was willing to take the credit during good days on the trail; on bad days, I was convinced one of them must have come up with such a crazy scheme.) Despite my supposed status as originator of the family thru-hike goal, I had many doubts about whether I could actually do it. When a friend who has known us for several years asked me at a book club dinner, “What will you do when Mary caves?” I assured her I was the weak link in this particular chain. I have always felt somewhat of an impostor among hardcore backpackers. Gary is the most competent person I know in backpacking, rock climbing, and mountaineering. He’s totally at home in the woods. And Mary is well on her way down the path trod by her father’s boots. Even before she set out to conquer the PCT, Mary was the youngest person to summit Mt. Shasta and to thru-hike the 165-mile Tahoe Rim Trail.

But I look at thru-hikers, especially the women who are strong enough and brave enough to hike long trails alone, and I think, “I could never do that.” I have to remind myself that I am strong and brave and skillful. I lived a full and occasionally adventuresome life on my own before Gary and I married. But sometimes I feel the way I did when I first joined Mensa, the high IQ society. For several weeks after I received the letter announcing I had qualified to join, I was convinced another letter would follow with an apology for their mistake. Months went by before I lost that nervous apprehension every time I checked the mailbox. Eventually, I attended a few Mensa gatherings and discovered I was as brainy as any other member. The same has been true of backpacking. I’ll read a trail journal by some woman who set out by herself when she was 60, or some man who went through the Sierra when every trail marker was buried under 15 feet of snow, and feel totally intimidated. And then I’ll meet those people at the Pacific Crest Trail kickoff or an American Long-Distance Hiking Association conference and realize that, hey, we have a lot in common.

Despite our ambitions, none of us was immune from worrying about whether we could—or should—try to thru-hike the PCT. I fretted about our ability to handle the physical challenges and, like many parents, nervously imagined how I would feel if Mary were to be seriously injured from a fall, bear attack, or lightning strike. Gary worried about the danger of one of us drowning during a stream crossing. He also worried how an independent-minded 10-year-old would behave when faced with day after day of discomfort, hard work, and enforced togetherness, aggravated by inadequate food and rest. Mary, aware of her father’s concern, mostly worried that the trip would be called off at the last minute. Gary was tempted several times to cancel it, but about six months before our projected start date, he made a commitment to go for it, no matter what.

Once we decided to do the trip, computer technology was a huge help in our preparations. Thanks to the internet, we could connect with experienced thru-hikers eager to weigh in on every aspect of the trail experience. Some long-trail veterans have journals online, and many of them are surprisingly personal. Many backpackers and trail fans participate in the PCT-L, an online forum that regularly hosts heated debates on everything from the best type of stove and fuel for long-distance hiking, to whether dogs should be taken on the trail. I conversed via email with a married couple in Pleasanton, California, near our home in Sunol, who completed the PCT in 2000. They were in their early 50s, just like Gary and me when we began. Marcia and Ken Powers went on to complete the Triple Crown: the PCT, the Continental Divide Trail (in 2002), and the Appalachian Trail (in 2003). And in 2005, they achieved the grand slam of long-trail backpacking when they finished the coast-to-coast, 4,900-mile American Discovery Trail. In the same way, I got in touch with a young man in Berkeley who completed the PCT in 1999. I read his online trail journal while he was hiking. After he finished, we exchanged emails with practical discussions about gear. Along with these seasoned backpackers, several trail publications provided essential guidance, most notably the three Pacific Crest Trail guides published by Wilderness Press, plus the accompanying Data Book; the Town Guide, published by the Pacific Crest Trail Association; A Hiker’s Companion, by Karen Berger and Daniel R. Smith, from Countryman Press; and Yogi’s PCT Handbook.

One of the questions they helped to answer was why more people don’t hike in groups. Why do so many start out alone? There are obvious benefits to hiking with at least one other person—safety, companionship, a second opinion on trail options, or a potentially cooler head in a pinch. And some thru-hikers are lucky enough to walk the entire distance with one or two others, usually spouses, sweethearts, or very close friends. But many have to plan for a solo experience. Why? Because hardly anyone wants to do it. In the years leading up to our trip, between 200 and 250 people attempted to hike the PCT each year, according to Greg Hummel, who keeps track of such things as part of his involvement with the American Long-Distance Hiking Association. He estimates that 50 percent of those people had the ability to finish, but only 30 percent to 35 percent actually did. So, something like 65 or 75 people might walk from one border to the other in a typical year. About 300 wannabe thru-hikers began the trail in our year; about 75 finished. The completion rate ranges from 60 percent in an exceptionally good year to about 10 percent for a bad one. Those are guesses, to be sure. No one knows for certain how many people start, how many finish, and how many are completely honest about having hiked the entire distance. By the time they reach Oregon and Washington, many former purists find themselves willing to skip small portions. A hiker might have to spend a few days in a motel room recovering from illness and want to catch up with his trail companions with a little hitchhiking. Or a thru-hiker might get a ride into a town stop, and then the next day someone offers to

drop her off a little farther along, perhaps avoiding one of the more unpleasant stretches of trail.

The solo nature of the long-trail experience comes as a surprise to many people. They’ll ask, “You hiked with a group, right?” What they expect to hear is that we signed up with some sort of guided tour, like a Sierra Club outing or an expedition on Mt. Rainier. But the Pacific Crest Trail, just like its sister long trails, the Appalachian Trail and the Continental Divide Trail, provides one of the few major outdoor experiences that is devoid of professional guides. This is a completely amateur undertaking. Now, to be sure, few people hike alone all the time. Those who don’t start out with a partner or spouse tend to form casual groups on the trail, as three or four hikers discover that they move at about the same pace and enjoy each other’s company. These groups are small and fluid, dissolving at town stops, re-forming a few days up the trail. The speed with which thru-hikers find themselves part of a community stems from this lack of hierarchy. There is no one whose job it is to look out for the rest, so we all look out for each other. But in the end, most thru-hikers have to be ready to be completely on their own for at least part of the trail.

During our research, we realized that every year, many experienced backpackers begin the trail with every expectation of success, only to fail. What makes the difference? Training? Motivation? Luck? Nope. It’s a simple matter of weather, and not even the weather during the hiking season. Rather, the biggest factor in completion rates is the snowpack in the Sierra Nevada. Since much of the Sierra’s snow falls in March, April, and even May, most thru-hikers have made the decision to hike in a particular year long before the size of the snowpack is known. Just the fact that we chose 2004, a pretty “normal” year for snowpack and for weather in general, was a stroke of good fortune for us. Subsequent years have been anything but.

Considering the time and expense involved in beginning a thru-hike, and the small chance of finishing, it’s not surprising so few people attempt to walk the entire PCT. The challenges are enormous, and the commitment is even bigger. All thru-hikers must train, buy gear, arrange to resupply along the trail, study guidebooks, and generally set aside their ordinary lives for five or six months. And for many thru-hikers (including us), there are additional headaches. We had to find reliable people to take care of our house, two cats, and a dozen or so indoor plants. I had to set up payment plans for the mortgage and other bills, and arrange time off from work. Mary had to finish all of her fifth grade class work 10 weeks ahead of schedule, which meant that as soon as she finished fourth grade, she began her fifth grade math, literature, and social studies at home. Luckily, the teachers and superintendent at Sunol Glen School were eager to help us in this regard, but what it meant for Mary was that she got no real summer vacation in 2003. Gary figured out what we would need in each resupply box, planned our town stops, and ordered all the gear. The financial hit can be substantial: By the time Gary replaced most of our old gear with the lightest, strongest, and warmest he could find, we were out thousands of dollars. That’s a big deal when your annual income is about to be cut in half.

By the time April 2004 rolled around, we were about as prepared as it was possible to be. We were probably the most prepared newcomers to the trail that year, mainly because we had to do so much extra to safely include a 10-year-old on an undertaking on the scale of a PCT thru-hike. Every possible safety issue had to be taken into consideration, and a child’s differing point of view had to be accommodated. We could never rely on luck. Thankfully, after all those years of hiking together, we knew what to expect. For example, a 10-year-old’s energy levels rise and fall differently than an adult’s, and rely more on her state of mind. At the beginning, Gary and I frequently took extra weight from Mary on steep uphill sections, especially in the desert heat. But Mary grew stronger as we headed north, while Gary and I developed a long list of ailments. By the time we reached Washington, Mary was carrying more weight, as a percentage of her body weight, than I was. But in April, of course, all we cared about was that the apparently endless preparations were finally over and all we had to do was put one foot in front of the other. Or so we hoped.

Once we started training, we discovered which bits of the avalanche of advice we’d received were the most important. One nugget that proved extremely important in guiding both my training and my actual experience on the trail was a chance quip by a longtime backpacker, Lipa, a retired park ranger and an experienced outdoorswoman. We ran into her on a training hike in Sunol Regional Wilderness, just a few miles from our home. She was planning to climb Mt. Whitney, California’s highest mountain and the highest point in the lower 48 states, for her 65th birthday. We told her about our plans. She listened approvingly, and then remarked: “Once you get to a certain level of physical fitness, the rest is all mental.” I took her words very much to heart and focused equally on physical fitness and mental preparation. I’ve met too many people who thought they could get by with just one or the other. Mary and Gary could train together frequently—Gary was a stay-at-home Dad, and Mary didn’t have all that much homework in fifth grade—but I worked full time and had to force myself to find opportunities for strenuous hikes with a heavy pack, or to work out on our one piece of home exercise equipment, a stepper.

Gary took charge of guiding the mental preparations for all three of us. I tend to rely too much on him to do the thinking, and also to provide the determination and motivation, for backpacking trips. Gary encouraged me to push myself beyond my comfort level, to hike in the rain (which I hate), to think ahead, to be more aware of my surroundings. During off-trail trips in the Sierra, he taught Mary and me to use the compass and topographical maps, watch for landmarks, figure out which drainages go where—in other words, to be prepared to save ourselves if he were hurt. Intellectually, I agreed that this was a terrific idea. But on the ground, breathing hard and going rapidly insane from mosquito assaults, it was all too easy to just turn the whole thing over to Gary. Gradually, however, I began to develop the right combination of determination, caution, and creativity. I learned when I could push myself to go farther—at the base of a 1,000-foot hill, for example, on a hot day, when what I really wanted to do was lie down on the fire road, put my cap over my face, and not move. I also learned when I should stop even before I really wanted to. This happened rarely, and usually only above 10,000 feet, where the thin air brought on a euphoric feeling that, like Julie Andrews, I could climb every mountain. Gary also pushed me to think in terms of solving typical backpacking problems, such as broken buckles or misleading instructions, by myself. (He didn’t entirely succeed. To this day, when something breaks or doesn’t make sense, Mary and I tend to turn to Gary first.)

The second bit of advice that helped me so much is a cliché I’ve heard so often that I had come to ignore it: Take one day at a time. It’s so common that a Google search brings up millions of hits. That is so trite, I had always thought. So banal. But it came to mean a great deal to me in the first few weeks on the PCT. As we struggled through the heat and rough terrain of our first 700 miles, I often asked myself, “Can I possibly keep doing this for another month? Another week?” The answer was often, “No way!” But if I asked myself, “Can I just make it to tonight’s campsite?” the answer was always yes.

As our departure date neared, we had one more major chore to confront: choosing our trail names. The use of special nicknames is a long-trail tradition, generally considered to have begun on the Appalachian Trail. Some people choose their own, some have them assigned by other hikers, and some don’t use trail names at all.

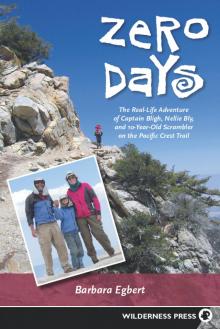

Mary acquired her trail name, Scrambler, in the time-honored way of having it given to her by other hikers—her parents. This happened on our second thru-hike of the 165-mile Tahoe Rim Trail in 2003, when we knew that we would be tackling the PCT the following year. We were heading down a very rocky section of trail near Aloha Lake, heading into Echo Lake. While Gary and I were making heavy weather of the bad tread, Mary was just skimming over th

e rocks, almost as though she were skating over the tops of them while her parents followed laboriously behind. “Look at her, just scrambling over the rocks,” Gary remarked enviously. And thus a trail name was born. We ran it past Mary, who liked it and promptly adopted it as her own.

Gary acquired his trail name from his daughter one evening a few weeks before we had to leave, while they were packing food, toilet paper, and other essentials into resupply boxes. He was, in her words, “bossing me around too much,” and she told him, “You’re just like Captain Bligh,” referring to the tyrannical captain in Mutiny on the Bounty. When I learned of the exchange, I endorsed the nickname because the real 18th century Captain Bligh was most famous as a navigator, and Gary’s wilderness navigational skills are superb.

I chose my own trail name, which is something many people do, sometimes as a pre-emptive strike against being stuck with something they don’t like. Nellie Bly, a name from American folk tradition, was the pen name used by the first American woman to be a true investigative journalist, back in the 19th century. She was an early hero of mine when I was growing up, and the children’s biography of her that I read probably had some influence on my decision to make journalism my career.

Zero Days

Zero Days