- Home

- Barbara Egbert

Zero Days Page 4

Zero Days Read online

Page 4

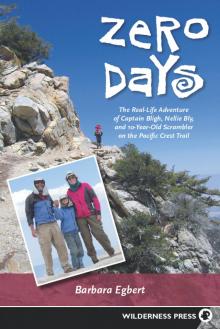

As a family, we became known on the trail as “the Blighs.”

Finally, we were ready to go—more than ready, in fact. Coping with the months of preparation, advance bill-paying, and arrangements to take off from work and school and to have the house and pets and cars taken care of left us with one burning desire: to start walking. So on April 8, 2004, a friend dropped us off at the border. We shouldered our packs, faced north, and began putting one foot in front of the other, on our way to Canada.

CHAPTER 2

TOGETHERNESS

Day 132: South Matthieu Lake. Today we spent the whole day cooped up in the rain. It was horrid to have so much togetherness.

—from Scrambler’s journal

IT FELT SO GOOD TO GET AWAY from the daily distractions and irritations of ordinary life. On the trail, we escaped from telephones, televisions, and computers; from bills, advertisements, and junk mail; from teachers and bosses; from paid work, housework, and homework. But we couldn’t escape from each other. We hiked together, ate together, slept together. Sometimes we even “went to the bathroom” together, our backs carefully turned toward each other to preserve an illusion of privacy, when there weren’t enough bushes to provide the real thing.

As much as we love each other, Gary, Mary, and I appreciate the ability to occasionally get away from each other at home. But on the trail 24/7, there was no escape. We saw each other all day. We listened to each other talk, eat, snore, and burp. We smelled each other as the days stretched out since our last showers. And sometimes, believe it or not, we got on each other’s nerves.

Adult hikers who travel as a pair or a group generally learn to respect each other’s hiking speed and style and often spread out along the trail during the day. One couple we knew left camp a couple hours apart to accommodate their differing abilities. They would wake up at the same time, but she would devour breakfast, dress, pack, and get walking as quickly as possible. He would get ready in more leisurely fashion, taking down the tent and doing most of the camp chores. Once he finally started walking, he usually caught up with his wife within a few hours. This approach worked well for them, although she had to make sure she marked her route carefully at trail intersections.

Some couples and even threesomes intend to stay together, only to discover early on how difficult it is for one person to match his hiking style to another’s. Standard advice: Don’t even try. If you want to hike with someone else, be content to share campsites and break stops, but don’t worry if you get separated in between. People hiking or doing any other task for hours at a time naturally settle into a speed that’s most efficient for them. Trying to adjust to someone else’s level isn’t just frustrating—it’s exhausting. Two people can start out the best of friends, but imagine how they’ll feel toward each other after a few weeks if their hiking styles don’t mesh.

Consider this scenario for two hikers—call them Eagle and Badger. Eagle gets up at the crack of dawn, packs up within half an hour, and puts in 3 or 4 miles on the trail before he stops to eat breakfast. Badger doesn’t wake up until the sun is high, cooks and eats a hot breakfast, then packs up at a leisurely pace. He might take 90 minutes to get out of camp—on a good day. Eagle moves fast but takes frequent breaks. With military precision, he sits down, eats a granola bar, drinks half a liter of water, and is on the move within 20 minutes. Badger walks for two or three hours between breaks, but then spends 45 minutes or so eating, filtering water, and treating his blisters. Eagle moves like lightning on the flats, slows on the upgrades, and crawls down the hills with aching knees. Badger moves at the exact same 2.5 miles per hour regardless of the terrain. Eagle stops only to take photographs, but then he might spend 15 minutes getting just the right frame. Badger doesn’t even carry a camera, but he’ll spend 30 minutes chatting with anyone he meets along the way. Force these two guys to stay together on the trail for more than a day, and watch out for the fireworks. But let them hike at their own pace, and when they meet in the evening to camp, they’ll get along great. Badger and Eagle will tell everyone later how lucky they were to find the perfect backpacking companion.

Gary, Mary, and I have different hiking styles, too, but we had fewer options than most hiking trios. Our rule was that Mary must be with an adult at all times. Frequently, we all three hiked together. I was a good pace-setter on moderate terrain, and often I would lead, with Mary (whom I generally addressed by her trail name of Scrambler) in the middle and Gary bringing up the rear. But if we split up, I was usually the adult who stayed with Mary. If Gary (a.k.a Captain Bligh) got ahead, he would wait occasionally for us to catch up, and he’d stop at any confusing trail intersections. But because of the size of his load, he couldn’t just stop and stand there; he had to find a suitable boulder on which to prop his heavy pack, which sometimes took a while. If the Captain fell behind, he usually caught up with us easily because of our frequent stops to take jackets off, put jackets on, adjust packs, or go behind a tree. Sometimes I became impatient with Scrambler, who initiated the majority of these pauses, but most of the time I was grateful that she and I moved at more or less the same speed. We chose 2004, when Mary was 10, to attempt our PCT thru-hike, partly because Scrambler’s speed and strength had increased to the point that she could keep up with Nellie Bly (that’s me) most of the time, and I hadn’t yet become too old and decrepit to keep up with her. Our joke was that we wanted to hike the PCT at just that magic point when Scrambler’s upward strength line crossed my downward one.

When she was younger, Mary needed a lot of cajoling to keep her moving. On the PCT, she just needed a lot of what Gary called “mindless chatter.” Mary loves to talk: It helps her keep going and takes her mind off the weight of the pack and the heat of the day. Gary does better without distractions. Listening to Mary and me talk endlessly about how we would design fancy costumes or plan a 15-course meal or redecorate our home if money were no object drove him insane. Sometimes we had to agree to let Gary stay a couple hundred yards in front or behind just so he’d be out of earshot. I’m somewhere in the middle on the talk vs. no-talk scale, but I did find that a half-hour quiet time each afternoon did me a world of good.

A typical conversation on a hot day on the trail went something like this:

Scrambler: Mommy, can we talk about the restaurant we’re going to open when we get home? Just pretend.

Nellie Bly: Sure, honey. Where shall we start?

Captain Bligh: Wow, did you see that hummingbird that just flew by?!

Scrambler: Yeah, Daddy, it was beautiful! Hey, Mommy, how about we call it the Hummingbird Restaurant and serve all-vegetarian food?

Nellie Bly: Sounds like a plan. Tell me more.

Scrambler: We’ll have pancakes and waffles and scones and muffins on the breakfast menu, and people could have them made to order while they wait, and you could bake them and I could be the waitress and Daddy could meet them at the door …

Captain Bligh: Wait a min—

Nellie Bly: Great idea, Scrambler. We could spend whole days dreaming up exotic kinds of food to serve, and if we stick with vegetarian, our ingredients won’t be all that expensive. And then we could offer lunch with all kinds of soups and breads and quiches. And we could hang hummingbird feeders outside all the windows for diners to watch.

Scrambler: Yeah, that’s a good idea! And we can have hummingbird-embroidered placemats and napkins and …

Captain Bligh: Hey, look at that lake down there! That’s the bluest blue I’ve ever seen!

Scrambler: Wow! Take a picture, Daddy! Hey, Mommy, we could have special desserts named after all our favorite places on the trail. Like Purple Lake blueberry pie. And Mt. Whitney chocolate cake.

Nellie Bly: Yes, and Golden Staircase ice cream sundaes. How about Mojave Desert broiled custard?

Scrambler: Yes, and Burney Falls blackberry shakes!

Captain Bligh: Don’t you two ever notice the scenery anymore? Here we are in one of the world’s most beautiful places, and all you can talk ab

out is food!

Scrambler: We notice the scenery, Daaaad! We can talk and see at the same time! We’re giiiiirls.

Captain Bligh: Aaaaggghhh!

Before we left home for the trail, Gary’s friends at the rock-climbing gym he visits every week teased him that his real goal was to drive me to divorce him after six months on the trail, so he could spend even more time climbing. I thought that was pretty funny. We did drive each other crazy once in a while, but we’d learned on previous trips how to get along in the woods. That’s not the case with every thru-hiking duo or trio. We heard of one couple who had completed the trail a year earlier, put together a slideshow, presented it—and then got divorced. Romantic bonds less binding than matrimony have also become unraveled on long trails.

Trail journals provide a window into the relationships between people who find themselves hiking together, not always by choice. One online journal I read revealed a hiker’s resentment at being forced (in his opinion) to take responsibility for another who began walking with him in the southern desert. At first he enjoyed her company, but eventually he came to fantasize about ditching her. Another journal contained a backpacker’s bitter words about getting into a town stop with another hiker, who pulled a vanishing act at the first opportunity. More common, however, are reports of deep friendships formed along the trail.

The social aspect of thru-hiking is very important to some hikers—so important, in fact, that when we chatted with a bunch of Appalachian Trail thru-hikers in 2005 in Maryland, they mentioned one solitude-averse hiker who had quit the PCT because he met only a dozen people in a week on the trail. He returned East to hike the AT again, where it’s common to see a dozen people in just one day. Millions of people walk on the Appalachian Trail every year, most for dayhikes or weekend outings. But somewhere between 2,000 and 3,000 attempt thru-hikes each year, 10 times the number who start the PCT. And thousands more are doing section hikes on the AT. Most backpackers plan their days around the 250 shelters along the trail, so the AT during the day can be almost as well-used as a city sidewalk, and the shelters at night can be as crowded as a Yellowstone campground on Labor Day. This scene isn’t for me. I loved going for days on the PCT without meeting any strangers, and I would go crazy if I had to share an AT shelter every night with eight or 10 other people.

Partnerships formed on the trail can become a wonderful source of companionship, but they can also become the cause of deep irritation. Gary insisted before we start that we all agree on one thing: We wouldn’t let anyone glom onto us. If someone occasionally opted to hike or camp with us, he said, that would be fine, but under no circumstances should we let anyone join our group to the extent that we would be expected to alter our schedule for him or her, or in any way take responsibility for another person. I thought at the time Gary was overly insistent on this point: What would be the harm? And how long could someone possibly stick around?

I realized how smart he was to insist on this policy later when we ran into one backpacker near Lake Tahoe who gave us cause for concern. He seemed friendly at first, but soon we noticed he was subtly trying to boss us around and take charge of our decisions. When we arrived at a popular backcountry campground that evening, he tried to tell us where we should set up our tent and hang our food. We chose our own site and stashed our food in our usual way. (Later, a bear tried to get his food, but ignored ours.) The following day, we drew ahead of him when we chose to tackle a 1,000-foot elevation gain at the end of the day, and he chose not to. We didn’t see him again. We did hear about another backpacker, however, who didn’t find it so easy to ditch this guy. The desperate hiker finally got up very early one morning, snuck out of camp, and walked 30 miles to escape the pest.

We were not strong hikers by PCT standards—we never reached the 30-mile-a-day pace many backpackers achieve—so we wouldn’t have been able to outrace a strong hiker really determined to keep up with us. And time-wise, we couldn’t afford to take unscheduled zero days to let an unwanted companion get well ahead of us. Luckily, the few people we met whom we disliked either fell behind or dropped out, sparing us any unpleasant confrontations.

For the most part, it was just each other we had to deal with, on and off the trail, which was good sometimes and not so good at other times. Niceness and politeness in particular took a severe beating during the last few weeks we spent preparing for the trail. It wasn’t easy for friends and relatives to be around us during this period, especially one friend who stayed with us the last few days and then drove us all the way to the border. Gary and I were up past midnight every night counting supplies, putting precise numbers of vitamin pills in Ziploc bags, estimating toilet paper use, and so on. Then we’d get up after only a few hours of sleep to get Mary off to school. What with the stress and lack of rest, we became the classic Mr. and Mrs. Bicker, snapping at each other and generally leaving behind all pretense of a respectful relationship. The stress didn’t end when we thought we were ready to leave the house. Our friend, Mary, and I were in our cars and actually had our seat belts fastened when Gary decided we couldn’t leave. He didn’t feel confident that every last little item had been adequately and redundantly and obsessively counted and packed and checked. We got out of the cars and I called my sister, Carol, in Carson City to let her know our arrival would be delayed by one day (we were going to leave one car at her house). I ordered Chinese takeout, and then we spent another night in Sunol. The next day we finally did get going.

Thru-hikers sometimes have to be brutally honest with each other. As the leader of our little group, Ol’ Cap’n Bligh had, on occasion, to lay out some unpleasant truths. Gary had been involved in two expeditions to Denali in Alaska—one successful, one not—and he knew from those and other experiences that an expedition is doomed if it has the kind of group dynamics that value niceness and politeness at the expense of honesty and attention to detail. He frequently challenged us, and his remarks sometimes seemed hypercritical. But hurt feelings are a small price to pay for safety.

Nine years earlier, when he was preparing for his first expedition up 20,320-foot Denali, Gary was anxious, short-tempered, and frequently frustrated with everything that had to be done. This climb was fulfilling a dream Gary had pursued for many years, and I naively assumed that the last few months would be a time of happy anticipation, rather like a child’s run-up to Christmas. Silly me. About two months before he was due to fly to Anchorage, I came down with a cough bad enough to send me to the doctor. He diagnosed bronchitis, and put me on antibiotics. Then Mary, just 16 months old, acquired a deep, racking cough unlike anything she’d ever suffered. This time, the pediatrician took a nasal swab, and the next day she gave us the shocking diagnosis: whooping cough. We’d all been immunized and, furthermore, we thought whooping cough had gone the way of smallpox and polio, no more to be found in the developed world. We were wrong. The next thing I knew, Mary and I were spending the night in an isolation ward at the Kaiser Permanente hospital in Walnut Creek. There, she had a little gizmo shining a light through her finger so her blood oxygen could be measured, and every few hours she coughed so badly that she would throw up. Gary got sick, too, and he and Mary were quarantined for a week at home while the antibiotics took effect. And in the middle of all this, our beloved elderly cat died. With Gary’s training schedule in disarray and his health in question, he seemed to me both insensitive and selfish. I really hadn’t grasped that with a major mountaineering effort in his near future, he had to look out for himself more than for us. He had to be picky and self-centered if he wanted to survive. But I didn’t know that. By the time I took him to the airport, I was ready to tear up the return half of his ticket.

So in 2004, it came as no surprise to me that we were at our worst during those frantic last days. But we were hardly unique in that regard. Many thru-hikers also start the trail in something less than an ideal frame of mind. There are others whose leave-takings with spouses are tense, whose parents are reluctant to let them go, who wonder if relati

onships will survive or erode during the next six months. Those people are out there, but they don’t talk about it on the trail. Once people start hiking, they generally shake off all those doubts and stresses, at least for the first few weeks. All that really matters is that they’re finally walking. Everything lies ahead, and only Mexico lies behind.

WITH THE STRESS OF PREPARATIONS finally over, we began our hike as a family. And, of course, as a family, the dynamics of how we behaved at home continued on the trail. A complete change of surroundings didn’t change the fact that Mary and Gary share many personality characteristics, including stubbornness. This made for more than one tense day in the backcountry. As for getting out of camp in the morning—well! Any parent who has ever shouted at a dilatory child to “for heaven’s sake, find your shoes and put them on before the school bus gets here” can understand perfectly well what it was like for us. (How Mary could misplace so many personal items in the confines of a 6-by-8-foot tent is a mystery to this day.) We accomplished many goals during our six months of hiking together, but achieving quick starts in the morning wasn’t one of them.

Nonetheless, backpacking as a trio was wonderful. We were never lonely, on the trail or off. The longed-for but sometimes disturbing phone calls home that thru-hikers make during town stops, with their reminders that loved ones are far away and relationships and responsibilities are being neglected, didn’t trouble us. Our most important relationships were moving up the trail right along with us. The PCT became a shared experience we can draw on for context the rest of our lives. A day featuring particularly heavy rainfall will always be “an Olallie day,” and an unexpected treat will be “like that Gatorade near Bear Valley.” If I want to warn Mary that a new acquaintance strikes me as untrustworthy, I need only say, “He reminds me of Zeke.”

Zero Days

Zero Days