- Home

- Barbara Egbert

Zero Days Page 5

Zero Days Read online

Page 5

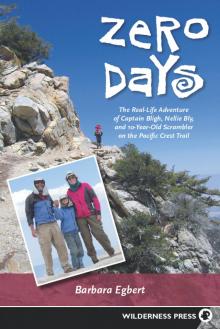

Having Mary along set us apart from the multitude of what some people refer to as “hiker trash.” Her presence guaranteed us a warm welcome and often an admiring audience at many of our stops. As a pre-teen attempting to walk from Mexico to Canada in one year, Mary inspired scores of parents to reconsider their own children’s outdoor experiences and ambitions. As trail celebrities, in a minor way, we occasionally enjoyed greetings such as, “Are you the famous 10-year-old?” (from a teacher hiking near Kennedy Meadows in the southern Sierra) and, “So you’re the famous family!” (from the postmistress at Belden in northern California). When everything from our feet to our feelings was hurting, the open admiration we encountered gave us a tremendous boost.

When we returned home, adjusting to routine life was made infinitely easier because of the shared nature of the experience. Solo thru-hikers in particular often find it terribly difficult to make that transition, because there is no one who can hold up the other end of the conversation. True, everyone asks questions, but they’re invariably the same questions. Once the returning hiker has explained how boxes of supplies are mailed to post offices and how food is protected from bears, conversations usually revert to the latest news about jobs and politics and vacation trips to Disneyland. As Triple Crowner Jackie McDonnell put it in Yogi’s PCT Handbook, her guide to all things PCT, “They’ll never understand.”

In our self-assumed role as crusaders for childhood exercise, Gary and I spent a fair amount of time talking to people we met along the PCT and explaining how it was that two 50-somethings and a 10-year-old could tackle a 2,650-mile trail. We told them all about our family values of exercise, good nutrition, and healthy living.

But as we worked our way up the trail, many of our other family values fell by the wayside or had to be adapted for the trail. I spent a lot of time thinking about these as we progressed on the trail:

EQUALITY: At home, I am the breadwinner, while Gary is a stay-at-home father. We spend most holidays with my family, but we fly East every year to visit his friends and relatives. I do the cooking, Gary does the laundry. I pay the bills, he keeps the cars running. We both wash the dishes. Sounds like the very model of a modern-day marriage based on equality between the sexes, but put us on the trail and it all disappears. I told Gary before we even started, “There are going to be times when I am too cold, wet, hungry, and miserable to even think. At those times, you will have to take charge, tell me what to do, and tell me in words of one syllable. Don’t worry about hurting my feelings.” Several times, I stood alongside the trail, cold, wet, and hungry, and moaned to Gary, “What shall I do?” Groan, whine, whimper. And Gary, who was also cold, wet, and hungry, would tell me what to do.

Now, I’m not totally insensitive. There were plenty of times when I resented Gary’s commands. I’d think to myself, just you wait until we get home! I’m going to tell you just where to put the dishes and just how to wash the clothes and just how to vacuum the living room rug! And I’ll use that same snarky, sarcastic tone of yours, you jerk. There were times when I thoroughly understood the homicidal feelings some people hold toward the leader of an expedition. Several years ago, I read the book Shadows on the Wasteland, by an Englishman who skied across the Antarctic with another explorer. The author, Mike Stroud, described his feelings on an earlier expedition—an effort to reach the North Pole unsupported by dogs, machines, or air drops—toward his partner, Ranulph Fiennes. Each pulled a heavy sled, and they had a gun to use against polar bears. It was clear from the start that Fiennes was the stronger of the two, and he was usually way ahead. This bothered Stroud. A lot. In fact, it bothered him so much that one day he concocted an elaborate plot by which he would catch up with his partner, pull out the rifle, and kapow! Death to the evil one. He would throw the body into the ocean, and make up a story about a polar bear and a frozen gun. He could call off the trip and still go home a hero. I never got quite to that point of resentment on the many days when I had trouble keeping up with Gary, either because I had to stay back with Mary or because I just couldn’t move that fast. On the other hand, I didn’t carry a weapon, either.

There were times when Gary reminded me of the tyrannical Captain Bligh in the movie version of Mutiny on the Bounty. But Gary didn’t want to be a trail dictator. Rather, he put considerable effort into teaching us how to be more independent.

It was a hard job. Take our packs. I thought because I had been carrying a backpack on our vacation trips for more than 10 years that I knew how to assemble one. Nope. I didn’t know squat. Gary had shown me how to pack, but somehow I hadn’t absorbed the reasoning behind the lesson. Finally, he had to line up Mary and me and give us a demonstration: light, bulky things like sleeping bags and down jackets in the bottom. Then the heavier things higher up, and close to the body. He repeatedly emphasized that point: Everything heavy should be packed so that it’s in the top half of the pack, and as close to the hiker’s body as possible. Water bottles should be arranged so they won’t slosh—and on hot days, they should be insulated with clothing to retain their morning coolness. Gary is a slow, meticulous packer, much to the irritation of more slapdash packers—me, for example. But once Gary gets moving, he doesn’t have to stop to adjust the contents of his pack. I started each day determined to emulate him, but it never seemed to work out. When Gary distributed items of mutual use among us, I ended up carrying each day’s food bag and the trowel bag, which contained the trowel, toilet paper, baby wipes, and Ziploc bags for used toilet paper. (We carried out all of our toilet paper so that it wouldn’t be dug up by animals or uncovered by wind and water. Too many popular backpacking routes nowadays are lined with used toilet paper, and we didn’t want to contribute to the unsightly result.) Every time we stopped, I had to pull out at least the food bag, probably the trowel bag, and frequently smaller items such as the foot-treatment kit, sunscreen, and insect repellent. I never could seem to get everything back in quite the same order as when I’d started. As a result, my pack would gradually become unbalanced and tilt to one side, adding to any other resentments I had picked up during the day.

A few weeks later, Gary gave us another lecture, this time about toilet paper. We had been on the trail more than a week since Kennedy Meadows and still had several days to go before reaching Vermilion Valley Resort, our next resupply point. I was suffering from a bit of diarrhea, so I was using more toilet paper than planned. Gary was shocked to discover we were getting low on the precious stuff, and even more shocked to learn that Mary and I fell into the category of people who wad up their t.p. before using it (a wasteful habit, in Gary’s opinion), rather than tidily and frugally folding it. Fifteen years of marriage, and he’d just now figured this out. This time, Gary lined us up and proceeded to give a drill sergeant’s rendition of Personal Hygiene 101. “You don’t have to use more than eight sheets of paper per day!” he exclaimed. “You don’t wad it up! You fold it in half, and use it, and then fold it in half again. And then you use it again, and fold it up and use it one more time!” All of this was accompanied by appropriate hand gestures and body posture to indicate how to accomplish the goal. Gary was dead serious about this. Running out of toilet paper is no laughing matter. But Mary and I couldn’t help ourselves. We kept seeing him through the eyes of a possible stranger traipsing down the trail and coming across our little tableau. We just couldn’t keep from giggling. However, we did take the lesson to heart, and rationed our cherished toilet paper carefully until we got to Vermilion Valley.

Stream crossings brought out the worst in me. Gary has good balance and can cross rushing streams on slippery rocks or teetering logs. Mary can, too. I take one look at anything less sturdy than an Army Corps of Engineers bridge and freak out.

Usually, our stream crossings went like this:

Captain Bligh: Well, don’t just stand there, look for a good way across.

Nellie Bly: Hmm …

Scrambler: I’ll just wade across.

Captain Bligh: No, you won’t. You’ll hur

t your feet on those sharp rocks. And it takes forever to get your boots and socks back on. Here, look, this log goes halfway across, and then you just step on that boulder, jump over there, and you’re done.

Scrambler: Hmph.

Nellie Bly: Looks impossible to me.

Captain Bligh: Just watch. … See? All done.

Nellie Bly: Hmph.

Scrambler: Hey, look at me!

Captain Bligh and Nellie Bly: Be careful!

Captain Bligh: Very good, Scrambler. Now you, Nellie.

Nellie Bly: I’m sure there’s a better place downstream …

Captain Bligh: No, there’s not. Now just come across or we’ll be here all day!

Nellie Bly: I’ll try … Oh! … Ouch! … Oof! … Aaaaggghhh!

Stream: Splashhhh!

THRIFT: Frugality was another family value that disappeared. It vanished long before we even got on the trail. On the “You might be a thru-hiker …” list posted at one trail angel’s home in southern California, an item reads, “If your REI dividend last year was over $150.” REI, or Recreational Equipment, Inc., is the giant co-op based in Washington state. (I think of the Seattle store as the REI mother ship.) It returns to each member a dividend of about 10 percent of what that person spent the previous year. For a family of three determined to replace every last piece of heavy, outdated gear with the lightest and most modern stuff possible, $150 is chicken feed. Our dividend from REI for 2003 was $318.18, and REI was only one of the many places we shopped. When it arrived in the mail, I just stared at it. I couldn’t imagine how we could have spent more than $3,000 at REI alone.

Gary and I dislike spending money. He buys his jeans from Goodwill, just like fashion-conscious high school students, although not for the same reason. I’m still wearing outfits to work that date from the Carter administration. (The trick is to change jobs every time the White House switches parties. That way, co-workers don’t notice how your wardrobe never changes, year after year.) But when it came to equipping ourselves for the PCT, money was no object. I had to stifle my objections every few days when I’d come home from work and Gary would tell me he had tracked down just the right jacket, or the world’s lightest ice ax, or that he had finally found a tent that would hold the three of us but still weigh less than 6 pounds. The credit card bills began mounting. And that was nothing compared to our on-the-trail expenditures. I’m famous for tracking down inexpensive motels—I once wrote a newspaper article about the techniques involved in finding cheap but comfortable lodging—and I’ve been trained since childhood to scrutinize the prices on a restaurant menu a whole lot more carefully than the menu items themselves. But those habits of a lifetime soon disappeared.

We started out well. Our town stop plans called for lodging at Motel 6-type establishments and eating at diners or fast-food places. But, oh, how that changed as we worked our way north. As most of the other thru-hikers fell by the wayside, so did our sales resistance. In Mojave, in southern California, we paid about $60 for a night at White’s Motel, and ate at McDonald’s. At Echo Lake, we bought sandwiches and fruit smoothies at the lodge, but eschewed the temptations of a motel night in South Lake Tahoe, camping at Aloha Lake, instead. At Belden, we cheerfully paid $85 for a cabin, ate any hot food the bar had to offer, and scoured the little store for extras. And by the time we’d suffered the rains of Oregon, we were ready for the Timberline Lodge on the slopes of Mt. Hood. I’m glad we slept and ate at Timberline, because we’ll probably never do it again. We could never afford it. Pay $125 for one small room? Fork over $25 for a plate of fish and veggies? Granted, fish at the Timberline isn’t anything like the stuff Long John Silver’s calls fish. Oh, no. Fish at the Timberline is baked Alaskan halibut in chipotle apricot glaze, with lobster risotto, pickled onions, and organic asparagus on the side. Or it might be Pacific ahi, crusted with toasted coriander and ginger, paired with a crispy macadamia nut sushi roll, Chinese snow cabbage slaw, and sweet orange soy reduction over more of that organic asparagus. And it’s not served by a pimply teenager stabbing a finger at the food symbols on a cash register, but by a waitress who’s pursuing a Ph.D. at Oregon State University in her spare time. On the other hand, we probably came out ahead by the time we finished breakfast the next morning. For $12.50 apiece, we got the all-you-can-eat breakfast buffet, and by the time we finished, all we could do was lie on our comfortable beds and groan. While we were eating, other lodgers came in, ate, and left, then more came in, ate, and left, then more. In all, we gobbled our way through the equivalent of three shifts of diners, and even got free beignets.

MANNERS: I tried. I really tried to develop a salty vocabulary on the trail. But my good Lutheran upbringing wouldn’t let me do it. I managed an occasional “hell” if I not only slipped on a boulder but banged both shins while crossing an ice-cold Sierra stream. And I managed to squeeze out a few “damns” here and there when the mosquitoes per square inch of skin exceeded a dozen, or when I stubbed a blistered toe for the tenth time in one day, or when I realized that the road crossing we’d just reached still left us 10 miles short of the campsite I had confidently anticipated seeing in just half an hour. But I never became any good at it. Gary, on the other hand, swore like the proverbial sailor, and used up the entire family’s quota of cuss words in an average morning. Mary, being 10, was the manners police officer for all of us. Ask the parents of most any grade-school child, and they’ll tell you how that works. Little Miss Enforcer never missed a chance to remind us that good manners could and should continue on the trail. And Gary never missed a chance to push her buttons.

Somehow, I always found myself in the middle of these discussions, which usually went something like this:

Captain Bligh: Burrrrppppp!

Scrambler (after waiting for a good three seconds): Daddy, say, “Excuse me.”

Captain Bligh: Daddy say excuse me.

Scrambler: Daddy! Say, “Excuse me”!

Captain Bligh: Say excuse me!

Scrambler (louder and more agitated): Daddy! Excuse yourself!

Captain Bligh: Excu—

Nellie Bly: Oh, shut up, both of you!

Captain Bligh and Scrambler (in unison): We don’t use that language in this family!

Nellie Bly: Well, excuuuuuuse me!

CLEANLINESS: Hah! Normally the kind of people who obsess over showers and clean clothes, we were the trail’s dirtiest hikers. Others somehow found time to take dips in lakes and streams, but slowpokes that we were, we always seemed to have barely enough daylight to get from tent site to tent site, eat, and sleep. It got to the point that Mary found clean people objectionable because the fragrance of their soap, shampoo, and deodorant was too strong. We have photos of our legs as black as obsidian from shorts-level to socks-line. We did wash our hands after every “bathroom break,” which is more than many backpackers can say. But without soap, our hands always looked grimy. And our fingernails were just filthy.

I hadn’t always felt so comfortable with dirt. When Gary and I first started backpacking, I insisted on taking along enough clean socks and underwear to put on fresh pairs every day, and enough T-shirts to change every other day. I would bathe in cold streams if nothing better was available. Gradually, I learned that I didn’t need clean clothes to survive, and that just because I smelled as bad as a three-day-old corpse, I wouldn’t automatically become one. On the PCT, we each carried two sets of clothing—shirt, underwear, and pants—and wore one set between each pair of town stops, saving the clean set to put on after our showers while the dirty clothes were being laundered. The one thing we carried an ample supply of was socks. We realized early on that dirty, gritty socks contributed to foot problems, and on many days in northern California, I spent my snack breaks washing socks in the dwindling creeks, downstream from where Gary was filtering water. We would dry the wet socks by hanging them over the horizontal straps on the outsides of our packs, cinched tight so nothing would fall off. In case there was any doubt, this clearly identified us as thru-hi

kers. After Captain Bligh spilled a bit of macaroni and cheese on his trousers during dinner, Mary wrote a brief journal entry that summed up the state of our personal hygiene: “Dad spilled food on himself. He thinks he’ll smell like sour milk. What’s the difference?”

Our hygiene was a little better when it came to food, although we occasionally ate something that had touched the ground briefly, as long as it didn’t look dirty, and there were no cows around. I forget who told us the M&M riddle, but it came to express my views pretty accurately:

Question: How can you tell different kinds of hikers apart?

Answer: Put a red M&M on the ground. A dayhiker will step on it. A section hiker will step over it. A thru-hiker will pick it up and eat it.

PRIVACY: In a tiny tent? Gimme a break. We did have our customs that provided a little privacy. I would wake up first, get into my clothes, and then wake the others. Mary, being so small, figured out how to dress inside her sleeping bag. Once we were both out, Gary would dress. But there were plenty of times when we all had to change clothes at once, and just ignore each other. Bathroom breaks were no problem during the first several weeks—we were among the first on the trail, and during April and May, we often went for days without seeing a soul. When nature called, I would just step a few feet off the trail and squat while Gary and Mary traveled on. (When it was Mary’s turn, I stayed with her.) But on the more popular sections, I got caught a couple times. Luckily, the two men near the San Joaquin River in southern California pretended they hadn’t seen me. The seven or so hikers near Thielsen Creek made believe that being mooned on the trail was just another part of the Oregon outdoor experience.

FOLLOWING THE RULES: For backpackers, Gary and I are on the obsessive side of the ledger when it comes to obeying regulations. We get permits to hike, we get permits to camp, we fill out all the forms, we follow the rules about fires, and we stuff our dollar bills in those little “iron rangers” if no live rangers are there to collect our money. We’re that way in private life, too. We pay our bills on time, drive the speed limit (OK, I go 5 miles per hour over), and never miss a vehicle registration deadline. We started out on the PCT with every intention of continuing our straight-arrow ways. Gary wrote in for our trail permits and paid for the Whitney stamps so we could climb the highest peak in the lower 48 states without worrying about hassles at the top. (Only a few thru-hikers skip the permit stage, but many don’t bother getting the Whitney stamp.) We generally camped where we were supposed to, never built a fire, disturbed no archaeological treasures, and harassed no endangered species.

Zero Days

Zero Days